Wildcat Cartridges

.309 JDJ

column By: Layne Simpson | December, 18

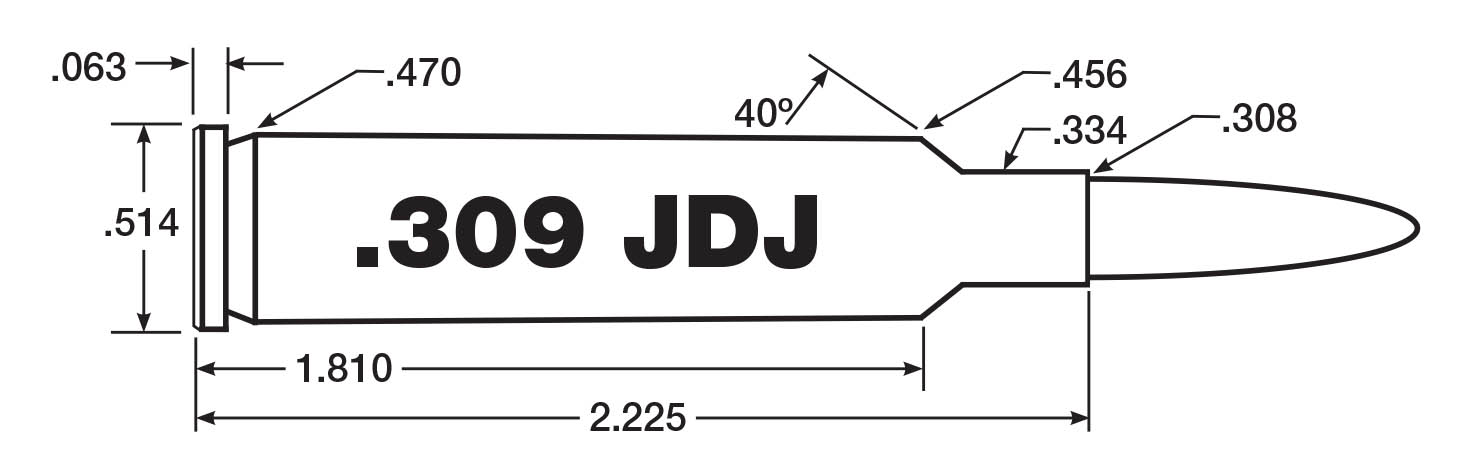

Except for their different bullet diameters, the 8mm, .338, .358, .375 and .416 JDJ cartridges are the same as their .309 littermate. All are formed by necking down a full-length .444 Marlin case. When a case is fireformed in the JDJ chamber, it emerges with a slight reduction in body taper and a 40-degree shoulder angle. There is not a lot of taper in the .444 Marlin case to begin with, so blowing it out to the improved shape results in a capacity increase of less than 4 percent, but the case is still surprisingly capacious. Gross water capacity is about 25 grains more than for the .30-30 Winchester, and 12 grains more than for the .308 Winchester.

Years later, I was reminded of Ackley’s experiments when rebarreling a Marlin 336 .356 Winchester to a wildcat formed by necking down the .307 Winchester case for flatnose 7mm bullets available at the time. When experiencing sticky case extraction at velocities much lower than the cartridge was capable of, I rechambered the barrel to an improved version of the same cartridge and reached my velocity goal with no sign of excessive pressure.

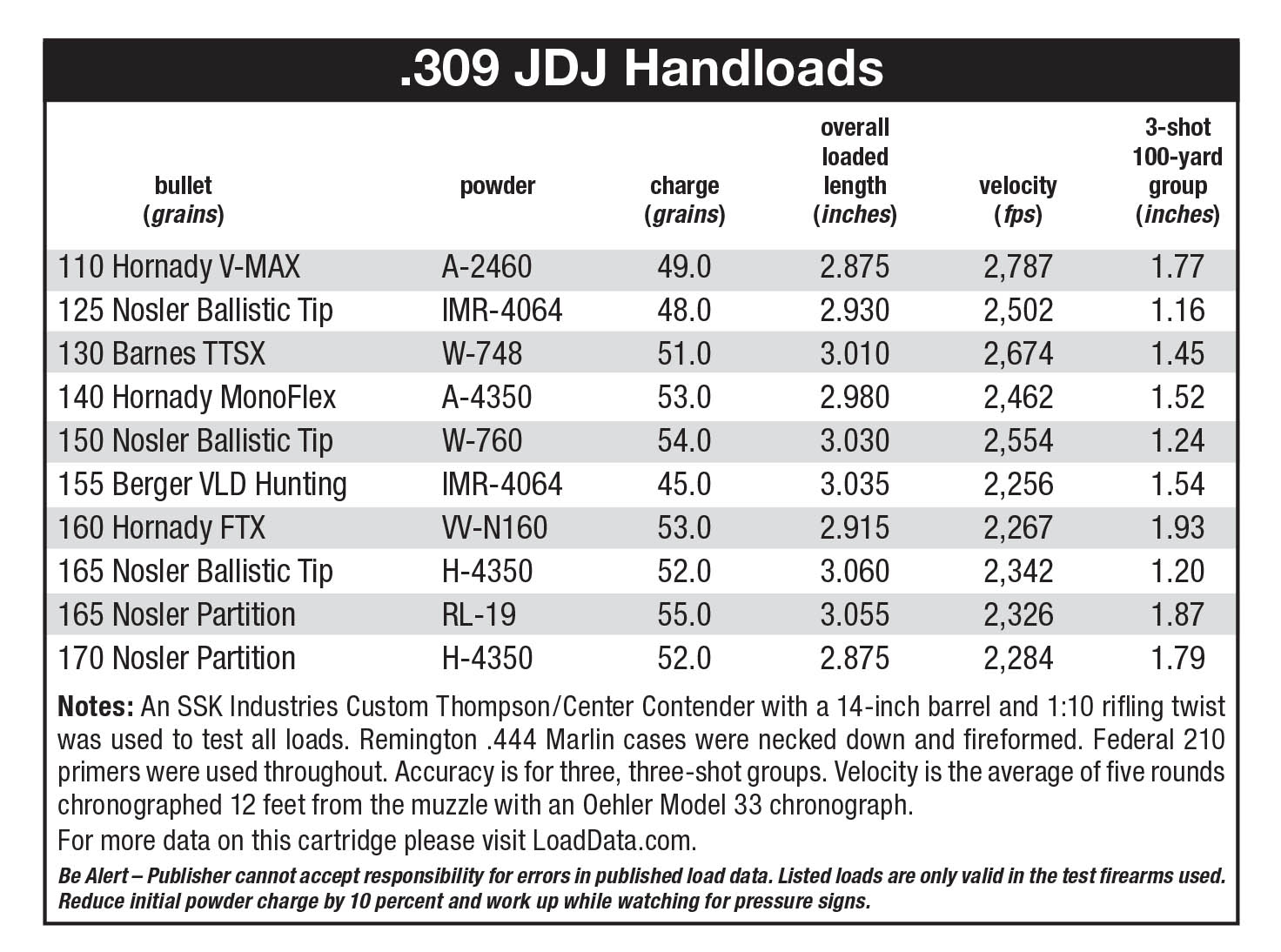

I used to hunt a great deal with handguns, and my most memorable adventure with the .309 JDJ was for barren ground caribou in Alaska. My handload consisted of a Remington case, Federal 210 primer and a Nosler 165-grain Ballistic Tip seated atop 52.0 grains of H-4350. Velocity from the 14-inch barrel was just under 2,350 fps. An Alaska-Yukon moose was also on the menu, and while the .309 loaded with a tougher bullet might have worked there as well, I stuck with the original plan of bumping off a moose with a Smith & Wesson Model 629 .44 Magnum. After using the revolver to take a very good bull at about 65 yards, I left it in camp and headed out for caribou with the Contender.

I had shot the .309 with its Burris 1.5-4x scope enough at home to know that 300 yards (prone with the gun resting atop my daypack) was about as far as I should attempt to shoot. Zeroed 3 inches high at 100 yards, the 165-grain Ballistic Tip landed about 12 inches low at 300 yards, where it delivered about 1,250 foot-pounds of punch; no powerhouse by any measure, but sufficient for caribou with good bullet placement. As the hunt turned out, I shot well enough, and the .309 was powerful enough, to take a bull at what most rifle hunters would consider a bit beyond the effective range of a handgun.

Due to its greater powder capacity, the .309 JDJ greatly exceeds .30-30 Winchester velocity and comes close to equaling the velocity of the .308 Winchester at lower pressures than that cartridge is loaded to. I also have a 14-inch .30-30 Winchester Contender barrel and a custom Remington XP-100 with a barrel of the same length in .308 Winchester. Depending on bullet weight, the .309 JDJ is 400 to 500 fps faster than the .30-30 and about 100 fps slower than the .308. The Contender action is not sturdy enough to handle maximum .308 Winchester chamber pressures, but due to the larger capacity of the .309 JDJ case, maximum charges of some powders used in it are close to the same weight as for the .308 at lower pressures. Hornady’s Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, (9th and 10th Editions) have more .309 JDJ data than any other source I have found, and they illustrate differences in capacities of that cartridge and the .308 Winchester. The T/C Encore will handle the .308 Winchester, but it is heavier and more bulky than the Contender.

There are several ways to form the .309 JDJ case, and regardless of which is used, the first step should be running brass through a .444 Marlin full-length resizing die to iron out dents and wrinkles. Next comes trimming

The body of the .308 Winchester case is much shorter, so begin with the .308 die in the press quite a long way from the shellholder. Then run a .444 case through the die and try it in the Contender pistol. If the gun will not close, continue turning in the die in quarter-turn steps while trying the case in the gun after each step. When it closes and locks up on a case, lock down the die and resize all the other cases. Do not fret if the shoulder has been pushed back a few thousandths too far as the case will headspace on its rim, and the shoulder will move forward during fireforming. For that, 47.0 grains of one of the 4350s behind a 150-grain bullet works fine. The .309 JDJ full-length resizer is used only after cases have been fireformed. Annealing the necks of cases prior to fireforming – and after every four or five firings – prolongs case life.

Remington cases are of excellent quality and are easy to form, but they can be difficult to find. Hornady and Starline cases zip through my two .444-caliber Marlin 336s without a hitch, but they are larger at the base than Remington brass and fit too tightly in my .309 JDJ Contender barrel. More specifically, Remington cases measure .464 inch versus .466 inch for Hornady, and .467 inch for Starline. Running them through an RCBS small-base .30-06 resizing die helps, but it does not totally solve the problem because the die is unable to reach all the way back to the front of the case’s extractor groove. Cases will chamber, but their fit is too snug for a quick, fumble-free reload during a hunt. Those formed from Hornady and Starline brass work perfectly in my SSK .375 JDJ barrel, so the chamber of my .309 JDJ barrel was obviously reamed to absolute minimum dimensions.

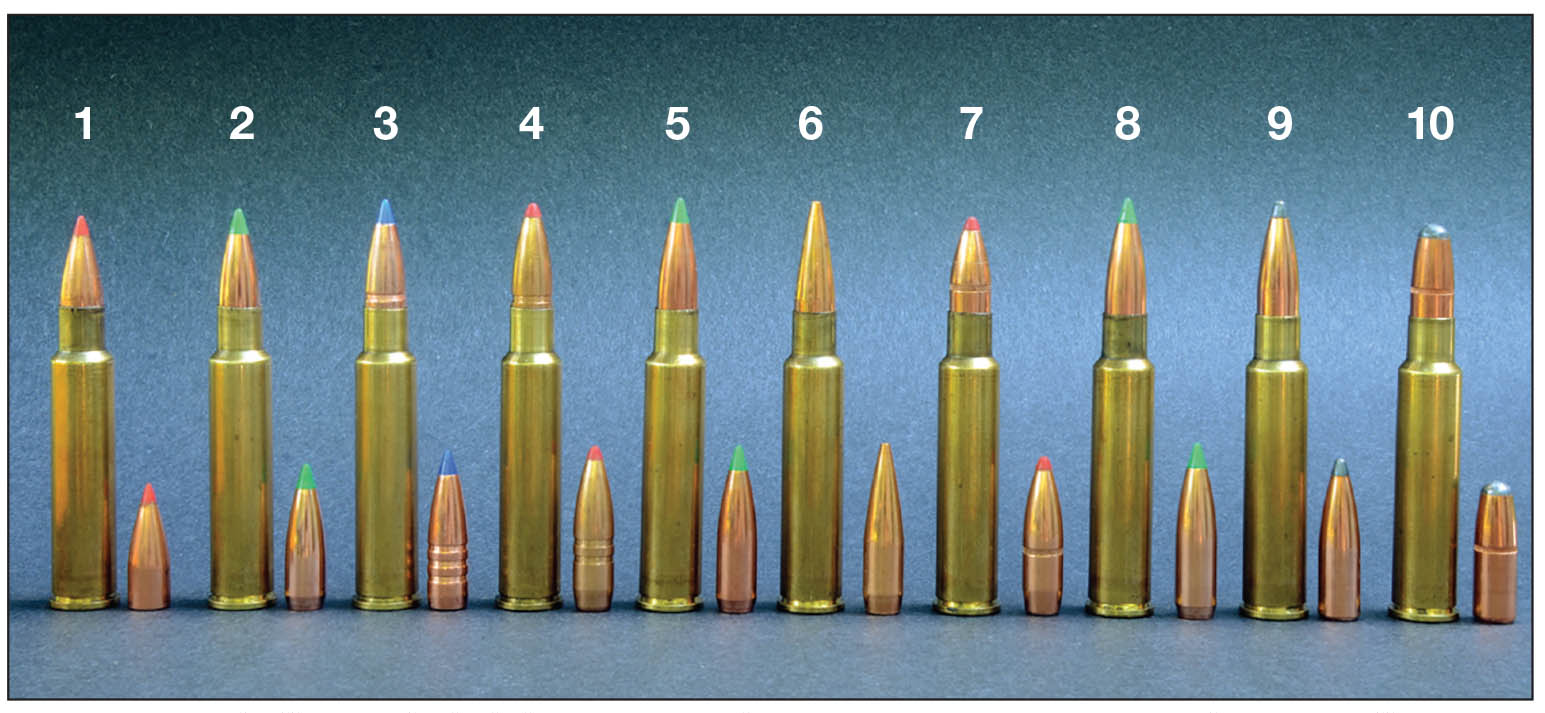

As favorite powders go, it’s a toss-up between RL-19, W-760 and H-4350, although W-748 is quite good behind the lighter bullets. I still like Ballistic Tips in this cartridge, but on future hunts I will try the Barnes 130-grain TTSX and the Hornady 140-grain MonoFlex.

My Contender is typical of those built by SSK Industries. It has a 14-inch Shilen barrel with 1:10 rifling twist and a Mag-Na-Port muzzle brake. Weight is an ounce over 5 pounds with a scope and T’SOB mount.