Swift A-Frame

Standing the Test of Time

feature By: Terry Wieland | December, 18

The A-Frame was one of a generation of bullets that came out in the 1980s and included the Trophy Bonded Bear Claw, Woodleigh Weldcore, A-Square Dead Tough and, a decade earlier, the Bitterroot. All were developed to fill what was becoming a more and more obvious void: A serious hunting bullet that could handle ever-higher velocities and still expand properly, hold together and penetrate to the vitals.

Meanwhile, Swift has gone from strength to strength. Located in an up-to-date production facility in the small town of Quinter in western Kansas, Swift now offers not only the A-Frame but also the Scirocco II. The Scirocco II is an ultra-streamlined, bonded design intended for precision long-range shooting, whereas the A-Frame is intended primarily for the biggest and toughest game at closer ranges.

The A-Frame dates from 1984. At that time, more and more hunting

John Nosler was the first to make an effort in this direction in the 1940s, and his work produced the Nosler Partition. The idea of putting a solid copper wall in the middle of a bullet was not new – the RWS H-Mantle from Germany was already famous – but Nosler brought the concept to America. The Nosler Partition has been a standard ever since.

Other bullet designers had other ideas. Bill Steigers, at Bitterroot, pursued the idea of bonding the lead core to the bullet jacket so that it would remain one cohesive piece as the bullet expanded. Bitterroot Bullets quickly gained a fine reputation for delivering beautifully mushroomed bullets, but there were three problems: They were expensive. Worse, limited production capabilities meant that it sometimes took years –

There was obviously room in the market for more players. Swift’s founder, Lee Reed, hit on the idea of combining the proven system of a “partition” (which, it should be noted, is a name registered by Nosler) while at the same time bonding the lead core. This would deliver the best of both worlds and ensure that the bullet retained a high percentage of its weight as it expanded. Typically, a Partition sheds the forward core as it expands and penetrates, retaining usually 60 to 65 percent of its weight. The A-Frame runs to more than 95 percent.

As all makers of genuine premium bullets have discovered, they require more operations and more labor. Consequently, they cost more to deliver. Nosler disguised the fact that Partitions cost twice as much as standard bullets by putting them in packages of 50 instead of the usual 100, so all the price tags looked comparable. It was a clever ruse (and in no way dishonest) and it worked. I know

For small operations like Bitterroot, Swift and Trophy Bonded, price was usually less of an obstacle than delivery. Of the three, Swift was the only company that really overcame that problem. As its reputation grew, so did the operation, and it was able to supply bullets to large ammunition manufacturers who then offered ammunition loaded with Swifts as a premium product.

Originally in the 1970s, there were two distinct hunting situations demanding better bullets. One was for high-velocity, small- caliber cartridges like the .270 Weatherby; the other was in really big, dangerous-game rounds like the various .416s and .458s, both factory and wildcat. Bitterroot aimed only at the first group. Nosler made Partitions as large as .375, but production in that caliber came and went, and the company made nothing larger for many years. Trophy Bonded, at one point, went as small as .243 and as large as .470 (and even made some experimental bullets in .224), but Federal has drastically curtailed the range of bullet diameters since it bought out the company 20 years ago.

Swift always covered the main part of the market, from .270 to .470, and has expanded the line in both directions. You can now buy A-Frames in .257 (100 and 120 grain) and 6.5 (120 and 140 grain), all the way up to both .505 and .509 to fit the .505 Gibbs, .500 Jeffery and .500 Nitro Express. In both .509 and .505, bullets are available in 535 and 570 grains.Makers of bonded bullets are reticent about how, exactly, the bonding comes about. It is almost always a proprietary process. Bitterroot was rumored to use epoxy; A-Square employed a form of solder; Jack Carter at Trophy Bonded developed a heat process combined with work-hardening. Since about 2000, almost every major bullet maker has come out with bullets billed as “bonded,” but not all behave as a real bonded bullet should.

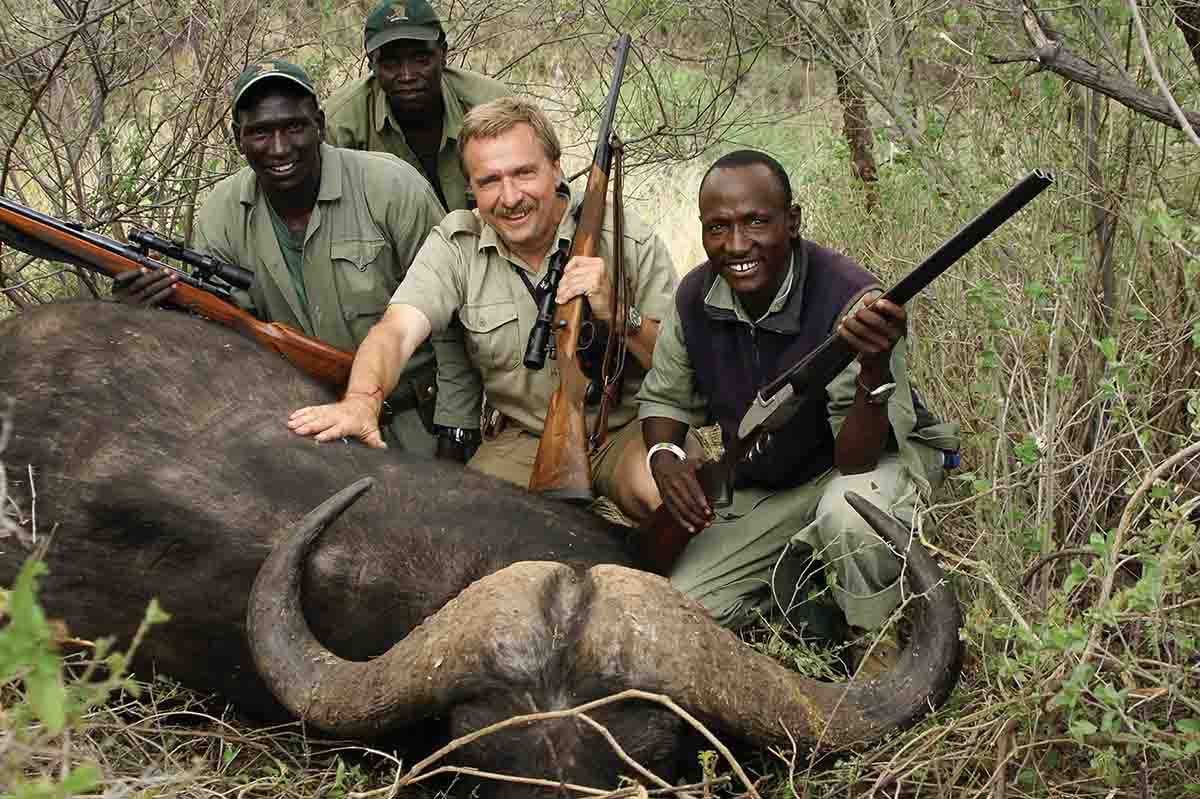

Swift’s process is also proprietary, but the proof is in the shooting. Swift bullets always, in my experience on game and in penetration boxes, expand beautifully and hold together with ferocious tenacity.

Experimenters learned early that the two materials that deliver the best results are pure lead and pure copper. Alloys of both tend to be brittle. They fracture and crumble on impact, where copper and lead behave almost like chewing gum, stretching and expanding but holding together. Unfortunately, copper is more difficult to work in its pure form, and it gums up machinery. This adds to time and expense.

Pure copper also behaves differently in bores. Because it’s soft, it plugs the lands and grooves more than does the harder, more slippery gilding metal. This can result – counterintuitively – in higher pressures. In recent years, with the advent of bullets made of pure copper or copper alloy, loading practices have become very specialized, with some data issued specifically for those bullets because they are long for their weight and produce different pressure patterns.

There is no particular secret to loading Swift A-Frames. The substantial copper wall in the center of the bullet does not produce pressure spikes or anything like that. They seem to compress in the rifling in a normal manner. As with any bullet by any maker, however, it is always prudent to start low and work up.

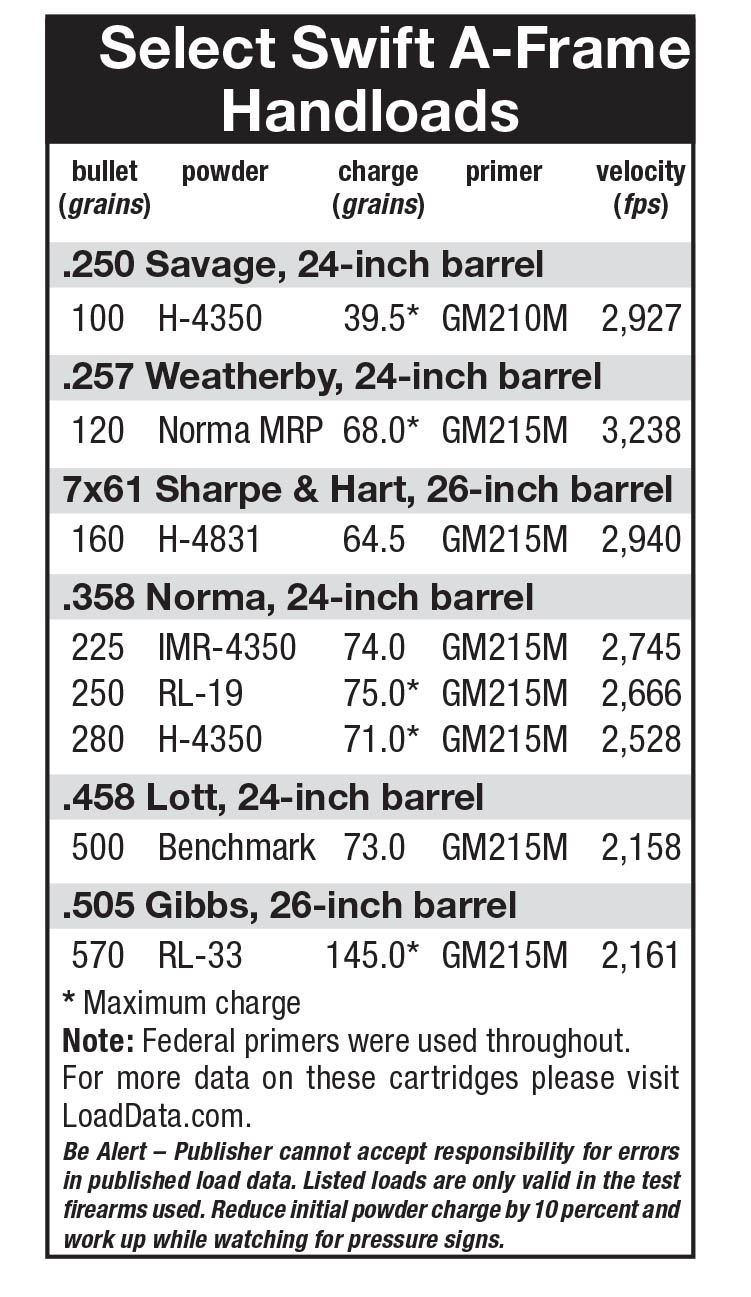

.250 Savage

The .250 Savage (.250-3000) is one of my all-time favorite cartridges, but it does have its limitations.Swift’s 100-grain A-Frame is a little too heavily constructed to work well in a Savage 99, where imitations include action size and maximum overall cartridge length. In a good bolt action, however, where the bullet can be seated farther out to leave room for more powder, the A-Frame gives the .250 Savage an added dimension, especially on tough and truculent animals like feral hogs.

.257 Weatherby Magnum

For anything larger than pronghorn or whitetails, I prefer a heavier bullet. The old Bear Claw was 115 grains, and I used it in Africa on wildebeest and zebra, among other things, and would not have hesitated to hunt elk with it. The Swift 120-grain A-Frame delivers comparable ballistics and results, plus it gives the .257 Weatherby ample power for anything in North America. I probably would not hunt the big bears with it, but that’s me. For feral hogs, the 100-grain A-Frame is particularly effective. My all-time favorite powders in the .257 Weatherby are Norma MRP and Reloder 22.

7x61 Sharpe & Hart

When Phil Sharpe released his darling to the world, it was loaded by Norma with a 160-grain bullet at a claimed (but not delivered) 3,100 fps. Realistically, it can drive a 160-grain bullet at about 2,950 fps without exceeding pressure limits, and Swift’s 160-grain A-Frame is perfect for the purpose. Of course, it works equally well in all the big 7mm cartridges.

.358 Norma

The .358 family has never been as popular as it deserves to be, squeezed from either side by the .338 and .375, and for this reason there has never been a wide range of bullets for it. A cartridge like the .358 Norma demands strongly constructed bullets. Fortunately, Swift offers three A-Frames in .358 – weighing 225, 250 and 280 grains. The 225-grain bullet is tailor-made for the .350 Remington Magnum, with its short neck and squat body, while the 280-grain bullet allows the .358 Norma to perform to its full potential and play in the same ring as the .375 Holland & Holland.

.458 Lott

I am a great believer in using 500-grain bullets in any big .450, but not in loading lighter bullets and trying to match the .416s. A 500-grain bullet makes the .450 into a big hammer, so why compromise that?

However, there is a wide range of .450s, but most of which are intended for dangerous (or at least hazardous) game. Swift makes four different weights in .458: 350, 400, 450 and 500 grains. Together, these provide a wide range of loading potential for anything from the .450 Marlin and .45-70 on the small side, all the way up to the .460 Weatherby and .450 Dakota. For the .458 Lott, the range of bullet weights makes it one of the most versatile cartridges in existence.

In 1994 the Swift company was acquired by Bill Hober, and since then he has steadily expanded both its operation and its products. Hober was the main force behind the design of the Scirocco II, as well as designing a new solid, the Break-Away. He bought out Ted Blackburn’s operation and now makes products such as bottom metal for custom gunsmiths. Swift also offers its own line of loaded ammunition and its own loading manual, now in its second edition. To its credit, the Swift manual includes both the .250 Savage and the .358 Norma – both cartridges that are unfairly neglected elsewhere.

From a standing start in 1984, the Swift Bullet Company has steadily grown and expanded, and can now be included in the select group of top-notch bullet and ammunition makers.