In Range

Forever Lite

column By: Terry Wieland | February, 20

Elsewhere in this issue is an article about reloading 2½-inch 12-gauge shotshells to use in unaltered English doubles. In the course of putting that together, I began searching around for some civilized loads to use in shotguns with standard 2¾-inch chambers, and guess what? They are almost as rare as the shorter English shells.

A glance along the ammunition shelf at my favorite clays range showed about a half-dozen different brands of 12 gauge, all intended for use on their lovely little wooded sporting clays course, and all (!) were loaded with 11⁄8 ounces of shot at a minimum of 3, and sometimes 3¼, dram equivalent, which puts the velocity in the region of 1,250 to 1,300 feet per second (fps).

Why, I enquired, did they not have at least one box of one-ounce loads at, say, 1,180 fps – a nice comfortable combination for going out and shooting 50 or 100 clay birds? The answer: Nobody wants those loads. They all want the heavier, faster, more powerful stuff.

By coincidence, at the same time I was re-reading a book of Gough Thomas’s (G.T. Garwood) columns from Shooting Times in England, published in 1971. He was responding to a reader’s plea for some way to relieve excessive recoil, and one of his recommendations was to move to a lighter load such as the Eley Impax one ounce, or even the 7⁄8-ounce Trainer. Even back then, these were hard to come by. Unfortunately, Garwood reported he’d gone into a gunshop near where he was shooting one time, looking for some of the standard Eley Grand Prix 1⁄16-ounce standard velocity loads. All he found was 11⁄8-ounce high-velocity ammunition. “We don’t carry the other,” he was told, “Because there’s no demand for it anymore.” This is an uncanny parallel with the situation I found – a full 50 years later!

In between Gough Thomas’s experience and mine lies five decades of writers like Garwood himself, Michael McIntosh, Steve Smith, Gene Hill, Bob Brister and who knows who all else, pleading with manufacturers to provide some light alternatives to their standard Roman candle “shot-grenades.”

In one of his books in the 1990s, Michael McIntosh even included an appendix on light 12-gauge loads, including all the load data required. Loading your own was pretty much the only way to get light loads then, although there were some glimmers of hope:

Estate Cartridge started up, offering a variety of light 2¾-inch loads, as well as some 2½-inch ammunition. RST (Classic Cartridge) did the same, and all the handloaders who were used to making their own “powder puff” loads could now buy good, off-the-shelf ammunition. Alas, the glimmers flickered and died. Estate was bought out by a larger company and now produces bargain-priced “club” loads but, as far as I can tell, the products that made the company famous in the first place have been abandoned.

RST is still around, and still offers a wide variety of stuff you can’t get elsewhere – 2½-inch ammunition and light 2¾ inch, and even some of each in paper hulls. Excellent, it certainly is; cheap, it certainly isn’t. As for Winchester, Remington and Federal, you’d think there was a federal law against civilized ammunition. They do make some, but none is as light as I’d like, and it’s hard to find.

What is being sold today as suitable pheasant loads seems to have been designed by ballisticians who see the word “pheasant” and think “pterodactyl.” They’re under the impression that a cock pheasant is as hard to bring down as a MiG-21. This delusion extends to ruffed grouse – one of the easiest birds to drop if you place your shot right – and even to quail and doves. From some of the so-called “Quail & Dove” loads now offered, you’d think a dove (or the typical pen-raised quail) was an airborne wolverine.

About 15 years ago, Bismuth Cartridge Co. set up to sell loads of so-called non-toxic ammunition, the Classic Double line, for use in older double guns. This stuff was about as suitable for a light double as stuffing nitroglycerine into the gas tank of a Ford. Obviously, whoever owned the company had no idea what a classic double even was, or what their prudent owners might like to put through them. The company didn’t last long, and no tears were shed when it disappeared.

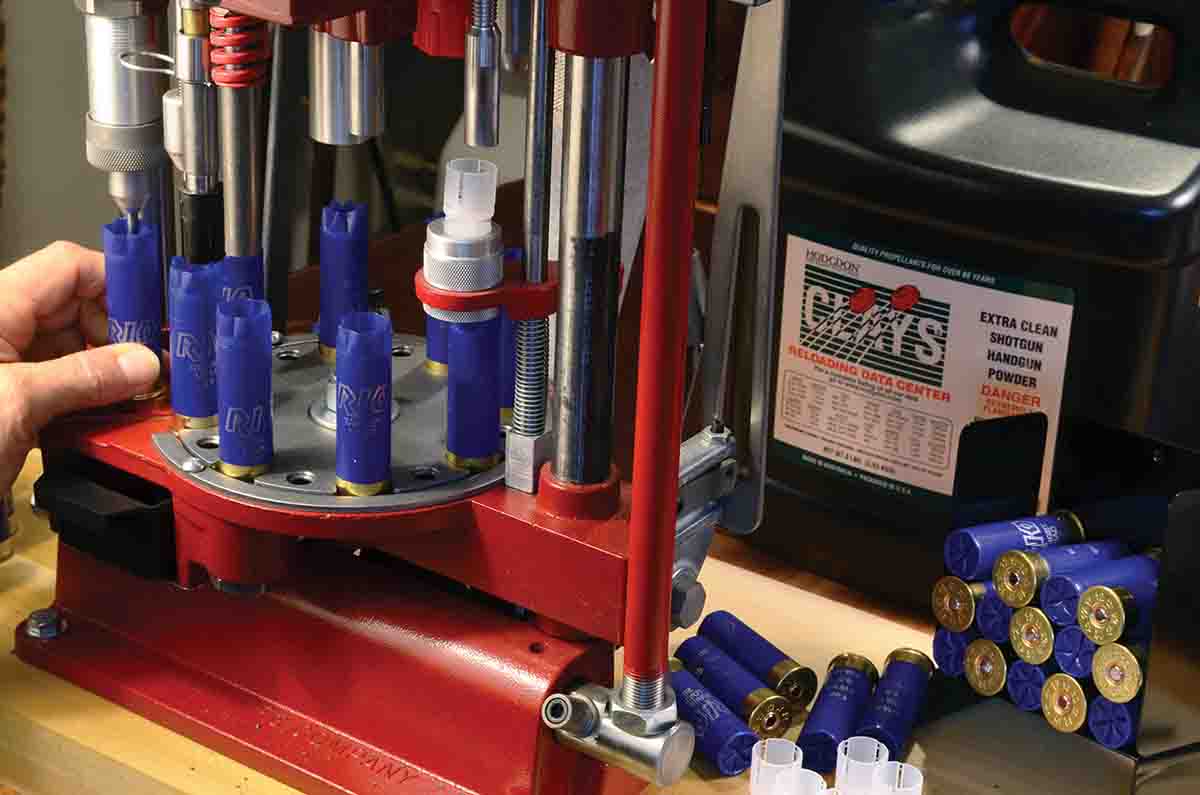

Today, we are right back where we were a half-century ago. If you want to shoot your dad’s A.H. Fox, the old Parker you found at a yard sale or the W&C Scott left to you by Uncle Bob, you have little alternative but to load your own. This is not because these guns are weak (they’re not) but because their relatively light weight makes them unpleasant to shoot in the volume needed for enough practice to shoot them well.

At one point, Gough Thomas applied his trained engineer’s mind to the question of just how effective a light load really is on game. He examined the 7⁄8-ounce Eley Trainer, a load of modest velocity intended for practice and for teaching new shooters. Based on likely patterns and pellet counts, he found that it would be a dependable bird-killing cartridge right out to 35 yards, beyond which it would become too scattered. He had earlier determined that each additional 1⁄8 ounce of shot added only 3 yards of practical game-killing range in a shotgun with the usual IC/M choke arrangement. Since the vast majority of game birds are killed well inside 40 yards, what more do you really need?

For the last 10 years, I have hunted wild pheasants in South Dakota with nothing but my dwindling supply of one-ounce B&P High Pheasant No.7. That particularly fine cartridge, imported from Italy, was discontinued about five years ago because the new B&P importer decided he did not make enough from selling its relatively modest volumes, and turned to filling his shipping containers with the American favorite: Heavy loads at high velocities.

Another of Gough Thomas’s observations was that the market for the heaviest shotshells mostly consists of younger shooters, who seem to believe a shotgun’s purpose in life is to put the maximum amount of lead into the air every time the trigger’s pulled, and that therein lies the secret of wingshooting success.

This, of course, is complete nonsense. Fred Kimble, the American market gunner who killed more ducks in a week than I will in a lifetime, offered this piece of advice: “The way to good shotgunning is practice and more practice.” The way to lots of practice is having lots of good practice loads that don’t pound you into oblivion. That alone is worth setting up your own shotshell loading operation – and these days, it’s about the only way to get them.