Cast Bullets and Battle Rifles

Handloading for the U.S. 30s

feature By: Mike Venturino | April, 19

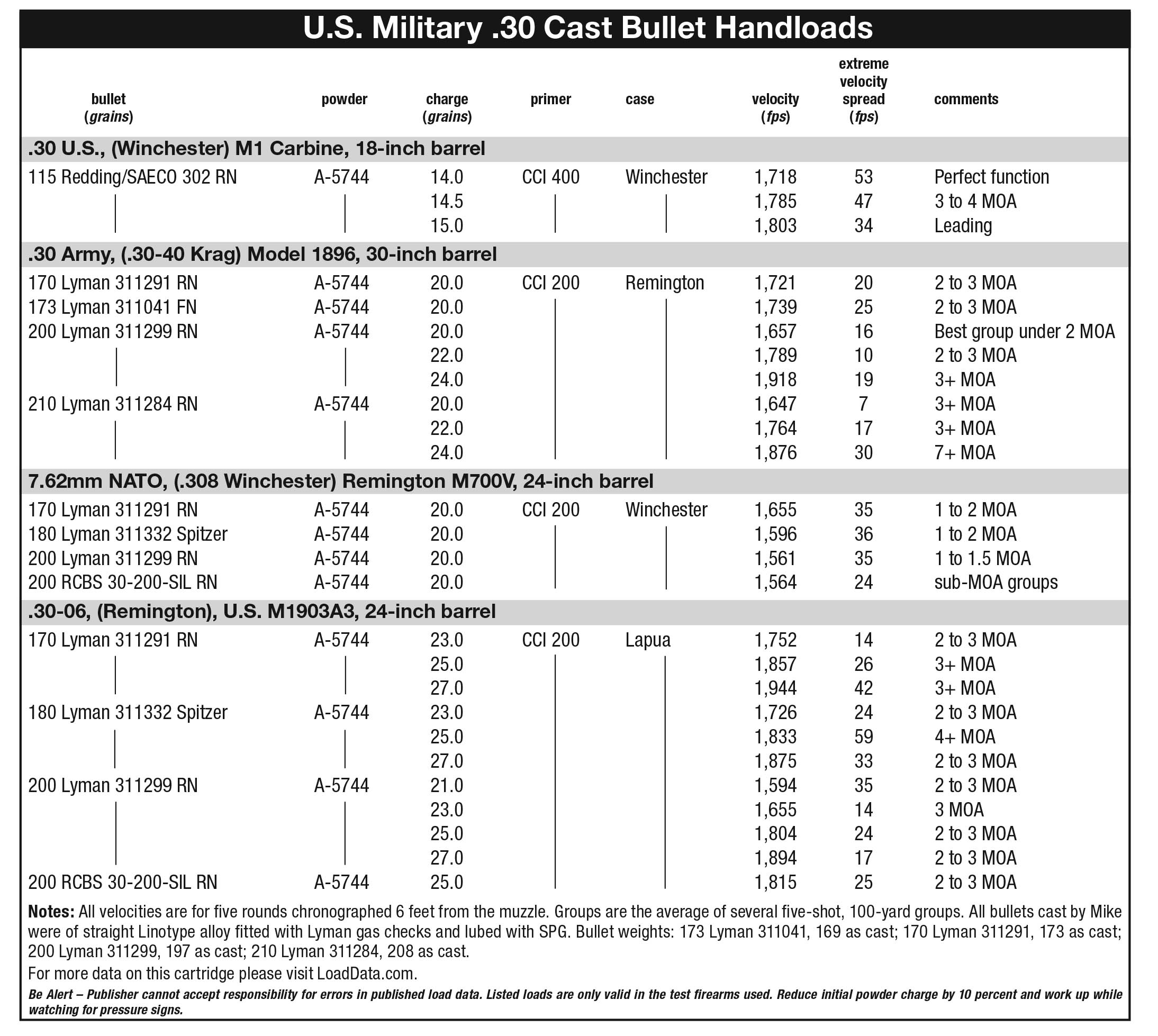

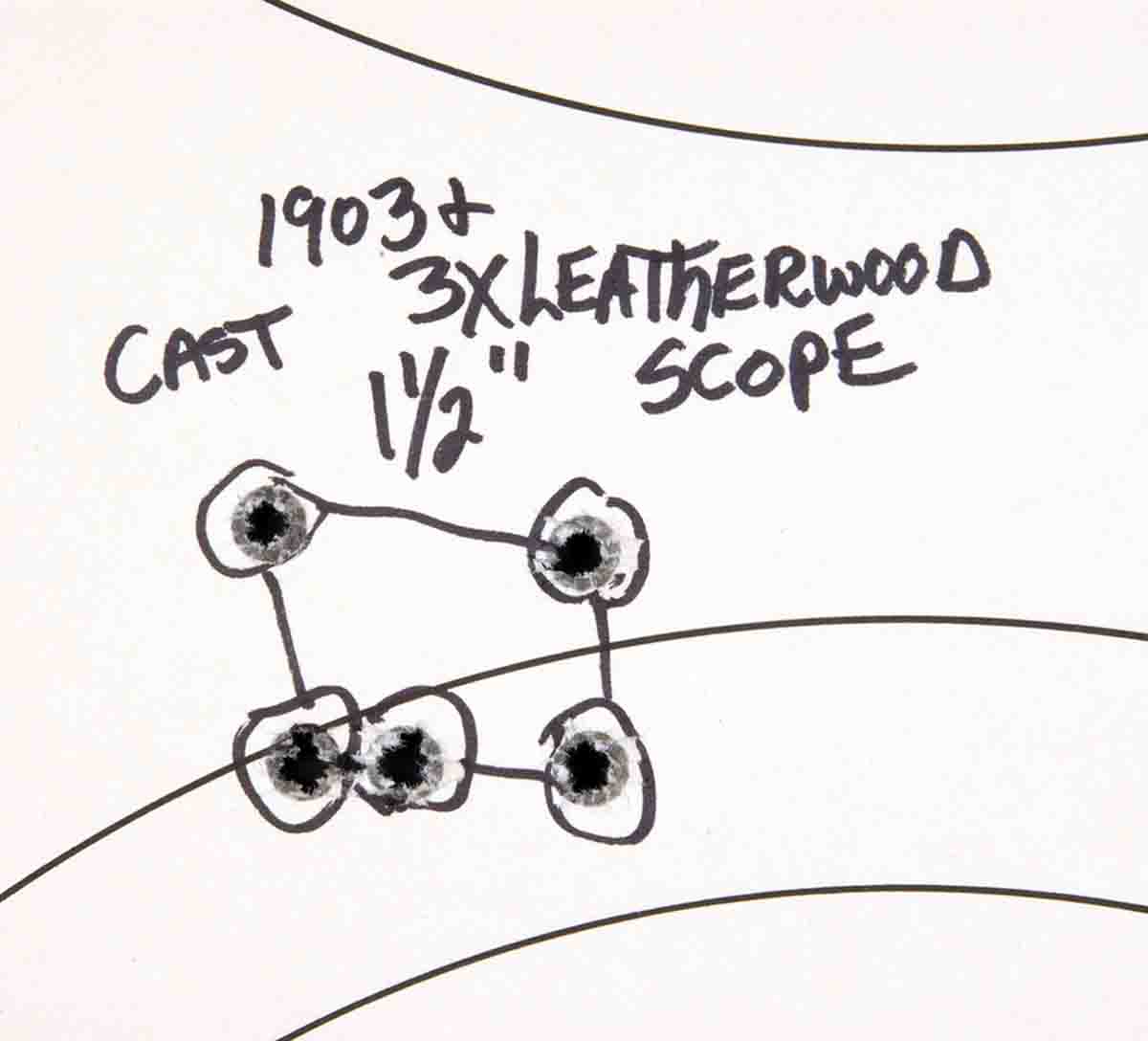

Except for the M1 Garands, I’ve fired cast bullets in every one of those rifles and carbines without a single failure. In fact, some loads grouped as tightly as good-quality jacketed bullet handloads and factory loads.

In 1892 the U.S. Army decided to adopt its first smokeless powder, bolt-action rifle. It was designed by Mr. Erik Jorgensen and Col. Ole Krag of Norway. Its

Whereas Mauser-style rifles in vogue elsewhere at that time had box magazines fed by five-round stripper clips, U.S. Krags had a “door” on the action’s right side that flipped open. Up to five rounds were individually inserted. When the “door” was closed a spring-powered follower pushed the cartridges under the action. The bolt picked them up for chambering from the left side. Krags quickly gained a reputation as the smoothest of military bolt-action rifles, albeit admittedly not the strongest.

The cartridge adopted by the U.S. Army set the stage for American .30s thereafter. Instead of barrels with a .303-inch bore such as adopted by Britain, Belgium and Argentina, American .30 bores were .300 inch. With rifling grooves .004-inch deep, proper bullet diameter is/was .308 inch. Those figures have remained in use on the .30-06, .30 Carbine and 7.62mm NATO.

In 1940 the diminutive .30 Carbine was developed by Winchester at the behest of the U.S. Army’s Ordnance Department. The government wanted a semiautomatic “light rifle” and dictated that its cartridge should have a 110-grain roundnose bullet at about 2,000 fps. Winchester based the new round on its .32 WSL (Winchester Self Loading) squeezed

Now jump to the early 1950s. Before the M14 became a reality, its chambering was already determined. With refinements in smokeless powders, military testers were able to get .30-06, 150-grain bullet ballistics from a shortened case. They called it the 7.62mm NATO. It had a case length of 2.015 inches compared to the .30-06 at 2.494 inches. Again, bullet diameter was .308 inch. By then a rifling twist rate of 1:10 was recognized as being faster than needed for 150-grain bullets. With the new M14, it was changed to 1:12 inches.

Now let’s return to cast bullets. Over the last half century I’ve shot lead-alloy bullets as light as 78 grains and as heavy as 215 grains in U.S. military .30s. Bullet designs have varied from flatnose, roundnose, spitzer, plainbase, gas checked, hollowpoint and likely others. Never, not once, has there been any difficulty in achieving good results with rifle barrels that were in good condition.

At this point I’d like to add a mention about the often-repeated caution that rifles will not shoot cast bullets well if any copper fouling remains in their barrels. I disagree. I’ve nearly worn out my right elbow cleaning some of my U.S. military .30s while cleaning patches still exited barrels colored green. Those same rifles shot cast bullets as good as I’ve come to expect any bullet to perform in military surplus rifles. At times I’ve fired 50 or so rounds of jacketed bullets through one and finished the day with a couple of cast loads without cleaning beforehand. Those last groups have never disappointed.

(Ideal Handbook No. 28 has a considerable number of interesting tidbits. Several of the .30-caliber cast spitzer designs are recommended for “shooting ducks.” One table indicates that a 150-grain Bronze Point .30-06 bullet at 3,000 fps will penetrate 18 pine boards of 7⁄8-inch thickness, but a 500-grain .45-70 black-powder load at 1,300 fps will penetrate 19 pine boards.)

The Hornady book states .30-06 case necks are .385 inch in length. The Lyman bullet No. 311299 measures .375 inch to the top of uppermost grease groove. Furthermore, when seated to cover the grease grooves, overall loaded length is 3.20 inches, well inside the overall loaded length of 3.34 inches listed by Hornady. At a weight of 197 grains when poured of Linotype, lubed and fitted with gas check, I consider bullet No. 311299 as ideal for the .30-06. It is also my favorite for .30-40 Krag.

Someone has to be thinking, But what about the .308 Winchester? Its case neck is only .304 inch according to Hornady’s dimensional drawings. That is exactly why I have great respect for the fellows at reloading tool companies who create good cast bullets designs. Consider RCBS silhouette bullet 30-200-SIL. From my mould using Linotype alloy, lubed and fitted with gas checks that bullet weighs 200 grains. Distance from its base to the top of its single lube groove is .303 inch. In other words, it is right on for .308/7.62 cast-bullet shooting, and of course it will work as well in .30-06s and .30-40s.

For a change of pace, consider the tiny .30 Carbine. When first loading cast bullets for an M1 Carbine about 40 years ago, Lyman mould No. 311316 was already on hand for loading .32-20 Colt SAAs and Winchesters. That mould dropped a flatnose, gas-checked bullet weighing about 110 grains. It is now discontinued by Lyman but worked well in that M1 Carbine. Early in this century, upon deciding to get into .30 Carbines again, I turned to Redding/SAECO for one of its excellent triple-cavity moulds, No. 302. It drops a 115-grain gas-checked bullet virtually identical in shape to the military 110-grain FMJ. It functions perfectly and is accurate from all of my current .30 Carbines.

In my years of loading for U.S. military .30s, powders tried ranged from Unique to H-4831. Most gave mediocre groups – not bad but just not great. Then in the early 1980s I was sent some military surplus powder labeled 5744. In short order I determined it was by far the best propellant for cast-bullet shooting in bottlenecked rifle cartridges. Velocity variations were low and accuracy was excellent, and even in large cases no sort of filler was needed to help ignition. Some loads left a bit of unburned powder in rifle barrels, but that didn’t affect shooting detrimentally. Putting a stout crimp on bullets did help with the unburned powder. All my cast bullet handloads for military rifles or sporters have Accurate 5744 in them, even the little .30 Carbine. I’m not the only one touting A-5744 for cast bullets. Lyman’s Cast Bullet Handbook, 4th Edition shows 5744 as the “accuracy” powder in a great many of its .30-caliber data sections, all the way up to .30-378 Weatherby Magnum.

Jacketed bullets cost about 5¢ apiece when I started handloading. Even at that price I could afford few. Today, .30-caliber factory bullets are running 30¢ and up. I can afford jacketed bullets now, but I like to cast bullets, and they only run a few pennies each. For simple fun shooting mostly at steel, they serve well.