Reloader's Press

Fifty Years with the .45 Colt

column By: Dave Scovill | August, 20

Since the Colt was already refinished and converted, it wouldn’t affect its value to convert it to .45 Colt. The price of the .45 Colt 7.5-inch barrel and a new cylinder from Numrich Arms/Gun Parts cost a bit more than the sixgun set me back in the first place. Fortunately, a gunsmith friend from college days, the late Clarence Beeley in Eugene, Oregon, offered to make the swap at no charge.

After the conversion to .45 Colt, the first three shots at 20 yards or so with Remington factory loads cut a cloverleaf group just above the point of aim and the fourth and fifth shots spread out a bit. That Colt, now fitted with a 4.75-inch barrel and a second cylinder with .452-inch chamber throats, has been in regular use since 1973.

Looking back, attempts to obtain acceptable accuracy with the first .45 Colt cylinder with chamber throats that averaged about .456 inch was a bit of a challenge, especially with those “hard” cast bullets that everyone seemed to be so fond of. It wasn’t until Elmer Keith autographed a copy of his SIXGUNS by Keith (1955) for my birthday in 1979 that I figured out what the problem was. His standard cast bullet alloy for .44- and .45-caliber Colt Single Actions, the latter with those .456-plus chamber throats, was melted-down .45-70 Government bullets, one-to-16 (tin/lead), Brinell hardness number (BHN) 8 with up to 18.5 grains of 2400 and the Lyman/Keith 454424 cast semiwadcutter.

It’s interesting that handgun scribes can quote Keith’s loads for the .44 Special, .45 Colt and .357 Magnum, but nobody quotes his bullet alloy. If anyone missed it on page 310, he repeats it three more times on page 311 in SIXGUNS by Keith.

With concrete information to go by, tests with the same bullet/alloy worked fine with the Lyman bullet seated over 16.5 grains of 2400, 13.2 grains of Blue Dot, 20 grains of IMR-4227 and eventually 10.2 grains of Accurate No. 5. I also adopted a load published by John Lachuk: 15.5 grains of now-discontinued W-630 with the same bullet.

It was my opinion at the time that Hornady’s 250-grain jacketed hollowpoint was the best choice for pressures and velocities that were suitable for the Colt SAA .45 Colt. When Hornady changed over to the XTP lineup with thicker jackets that were more adaptable to heavy loads in the Ruger Blackhawk .45 Colt that debuted in 1971, the Sierra 240-grain JHC and the arrival of the 250-grain Nosler Sporting Handgun hollowpoint proved to be excellent options.

Eventually, the 250-grain Speer Gold Dot offered another option. They all averaged close to .4515 inch, which required quite a bit of bump to form a gas seal in the chamber throats.

There is also an inventory of Remington and Winchester .45 Colt factory loads with the standard 250- and 255-grain RNFP hollowbase slugs, respectively, that fit those oversized chamber throats in older Colts and replicas out of Europe.

As a rule, the loads listed above are carried in appropriate revolvers at any given time. If I really thought I might stumble onto a bear that needed killing in the Lower 48, I would stuff the handgun in my back pocket and carry a bear-thumping load in a big-bore carbine, rifle or shotgun.

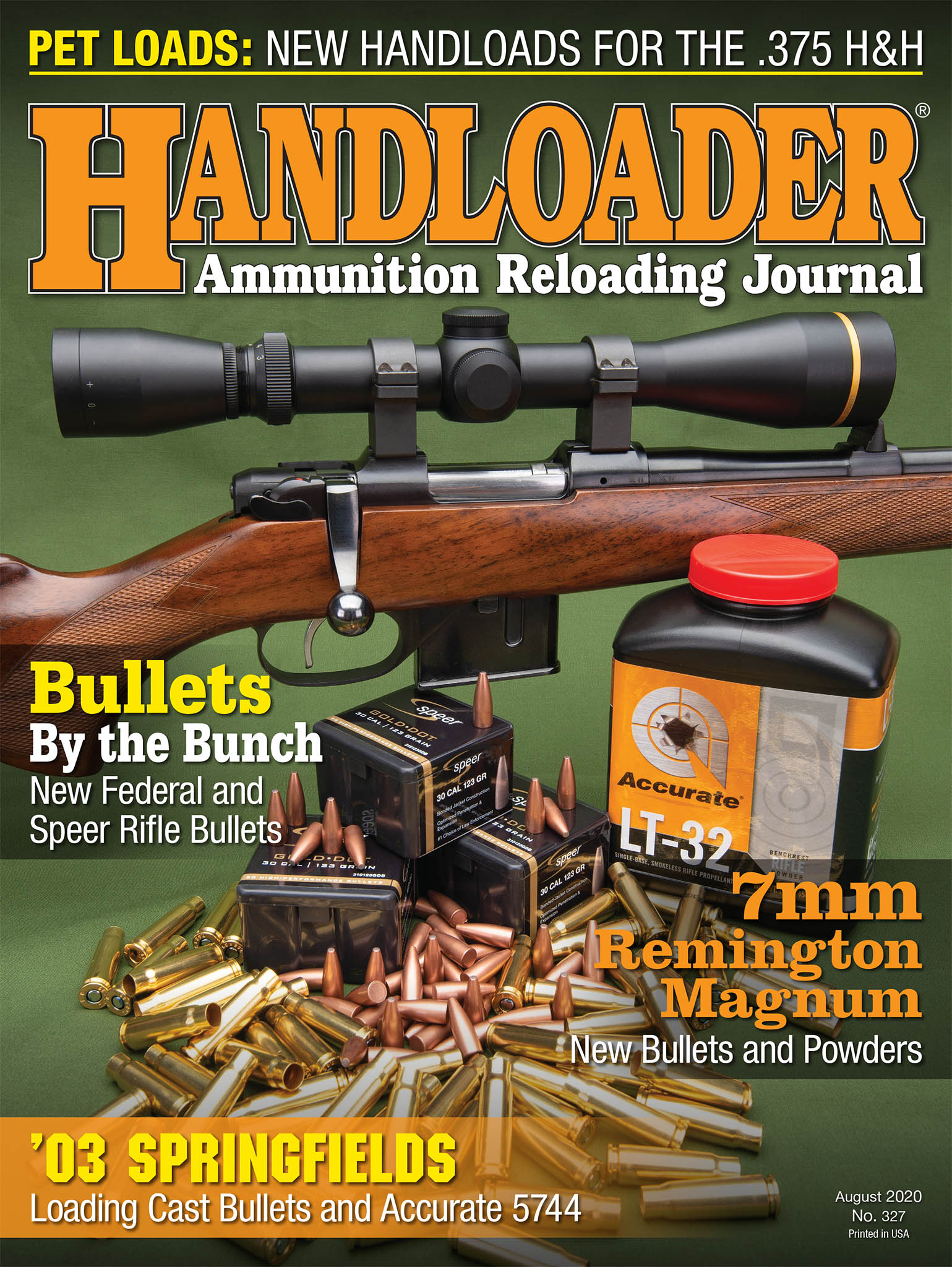

The photos of sixguns selected at random illustrate the variation in chamber throat and barrel groove diameters in double- and single-action .45 Colts. European Colt pattern single actions generally mirror measurements for the third generation Colt SAA.

The point to be made with nearly 50 years of experience with the .45 Colt and chamber throat and barrel measurements that vary by make, model and year, is that folks can ponder and fiddle around as much as they like with handloads, but if the bullets don’t provide a near fit with the chamber throats, regardless of how much they might like the hard-cast or jacketed bullets sized to fit the barrel, a lot of time can be wasted in attempts to make those guns shoot.

The big problem with hard-cast and jacketed bullets that are .005 inch or so smaller than chamber throat diameter and don’t bump up to form a gas seal is that they accelerate through the throat at random angles from one shot to the next and exit the barrel the same way. They might provide some measure of accuracy, say 2 to 3 inches, out to 15 to 20 yards or so, but they scatter like quail as the range increases. For whatever it might be worth, that’s at least one good reason a lot of folks think handguns are not capable of long-range accuracy; aside from marginal shooting skill, the load is no good to start with.

The Colt SAA (1906) with walrus ivory stocks is the first generation sixgun mentioned above that was converted from .38 Special to .45 Colt. Chamber throats measure .452 inch and barrel grooves are .451 inch. That Colt was refurbished about 20 years ago by Turnbull Restorations due to wear and tear, largely from extensive (not excessive) recoil with 16.5 grains of 2400, and the forcing cone in the first .45 Colt barrel was badly eroded by flame cutting, mostly from the use of hard-cast bullet alloys before I knew better.

The other SAA Colt shown with hickory (pickax handle) stocks is a circa 1916 .45 Colt. It has the standard .456-inch chamber throats and a 4.75-inch barrel with .451-inch grooves. Black hard rubber, aka gutta-percha, factory stocks were on it when I acquired it some 20 years ago. The previous owner advised that it had been stored in a drawer for 40 years or more where he lived in South Texas.

The stocks shown on this old Colt are another story. Roughly 45 years ago the gutta-percha stocks on the first Colt .38 Special were starting to crack around the screw holes. While scrounging around in the barn for a piece of scrap wood to make a pattern for stocks, a broken pickax handle appeared to have enough wood in it to make two halves to be glued together for one-piece stocks. The flared end of the broken handle was sawed off, then sawed down the middle. Both halves were thinned from the center outward then joined with a center piece and shaped to fit the Colt grip frame. Of course, it wasn’t that simple, but that was the basic job.

Once the stocks were roughed out to a somewhat oversized shape, they were thinned a bit and tried several times during firing tests. It took a while until they fit my hand and allowed a proper grip while cocking the hammer with the thumb of the shooting hand (left or right), pulling the trigger and cocking again without relaxing what should be a firm hold with three fingers gripping the stocks.

As luck would have it, when the 1916 Colt required a set of stocks, the hickory stocks were a near perfect fit – which is rare between two different Colts. So, in spite of the fact that they have been the source of ridicule, to wit: “Who’s the idiot that made those stocks?” since a photo of the first Colt appeared in the 1984 issue of Handloader Digest and a few times in Handloader since the early 1980s, they are still in regular use, and new stocks were fashioned from walrus ivory nearly 25 years ago to the same dimensions used with the hickory handles on the first Colt. For general interest, third generation Colt “eagle” stocks that appeared after the hickory and ivory stocks were made have similar width and shape.

The double-action revolvers mentioned above are all fitted with Herrett stocks that were shipped a bit oversized and worked down a little at a time for a custom fit. Fast and accurate double-action shooting would be nearly impossible with the factory stocks. The Triple Lock is used with the Remington 250-grain RNFP on occasional small-game sojourns (aka walkabout) in the Arizona brush country.

Earlier-style Bill Lett stocks shown on the Old Model Blackhawk were (are) slightly oversized and offer a near perfect fit for my hands. The Ruger Vaquero is also fitted with earlier Lett stocks that help absorb recoil from heavy .45 Colt loads much better than factory stocks.

The second observation to be made after 50 years of experience is that again folks can pontificate until the cows come home, but if handgun stocks don’t provide a good fit with the shooting hand, you can waste a lot of time and effort attempting to achieve best accuracy, regardless of how good the load may be. For folks who would like a second opinion, review Elmer Keith’s book SIXGUNS by Keith.