The .22 K-Hornet

Loading Lysle Kilbourn's Troublesome Pet

feature By: Terry Wieland | August, 21

In a 1975 Pet Loads article, Ken Waters announced his intention of setting the record straight as to the Hornet’s origins, and did so, to my satisfaction, at least. Since Waters was in the enviable position of knowing some of the principals personally, or knowing other people who did, I would tend to believe him. He had nothing to gain in lying.

Which brings us to the topic of this article, which is the puzzling little beast known as the .22 K-Hornet. About the K-Hornet’s origins, there is no mystery whatsoever: Ballistic guru Lysle Kilbourn developed it in 1940 by opening up the chamber slightly and blowing the Hornet’s case out to a straighter, sharp-shouldered “improved” version.

Denials to the contrary, the .22 Hornet case with its substantial rim and long sloping shoulder is simply the .22 WCF with a different headstamp. The one notable difference is that the original WCF bullet was .228 inches, which was the standard for centerfire .22s in that era (the same as Savage’s .22 High Power.) Probably to make things convenient, the Hornet’s bullet was reduced to the diameter of the .22 Long Rifle, thereby allowing the use of existing .22 rimfire barrels. As often happens, however, short-term convenience translated into long-term headaches.

These headaches include varying bore diameters, twist rates, bullet diameters and case capacities, all of which have plagued us over the years. With the K-Hornet, these were magnified by the fact that Kilbourn himself introduced later variations by moving the shoulder; as well, other gunmakers made little changes to suit themselves. While you may find a set of “standard” dimensions for the K-Hornet, these may (or, just as likely, may not) work with your particular rifle.

Evidence that the original .22 Hornet was based on older, thinner, black-powder brass lies in the fact that around 1950, manufacturers beefed up Hornet brass to make it stronger. Since external dimensions had to remain the same, this meant reducing case capacity, which in turn meant that older loading data (much of which was nudging – or exceeding – absolute maximum in those hairy days of yore) could, and did, become positively hazardous with the new brass.

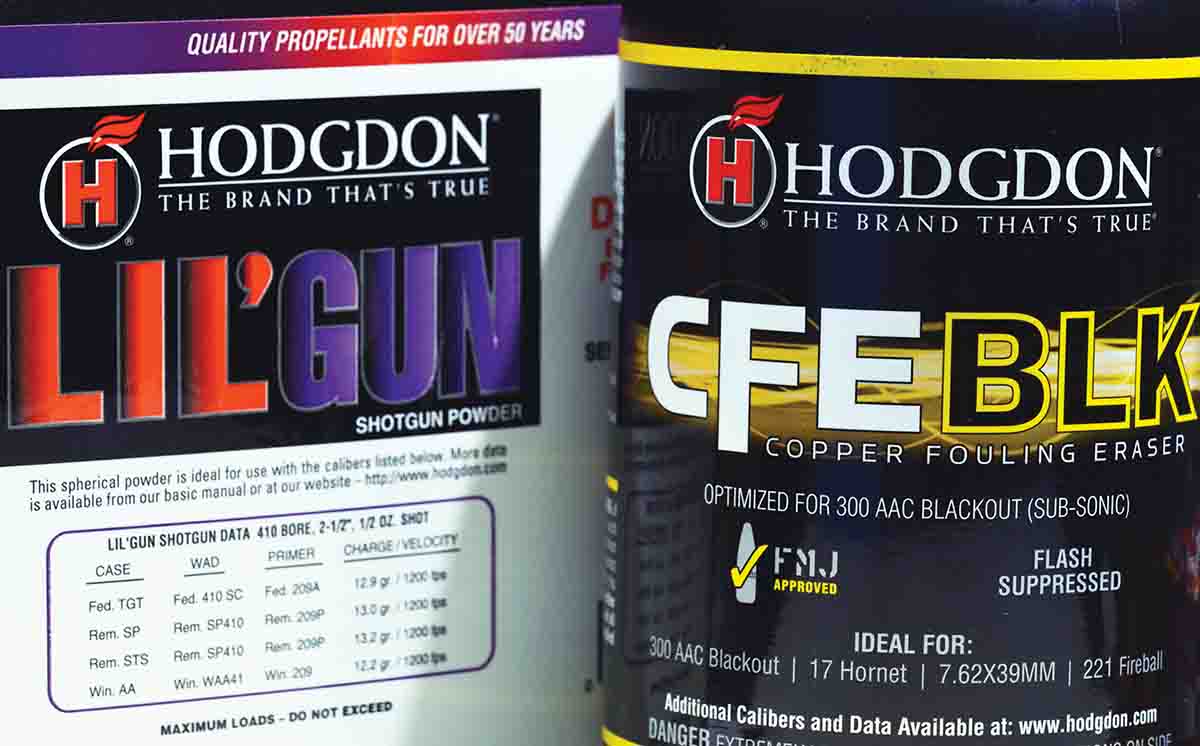

Using Hodgdon’s Lil’Gun as the measuring medium, I filled a Federal Hornet and a Federal-based K-Hornet to the mouth of each case. The Hornet held 14.2 grains, the K-Hornet 15.4. A difference in capacity of 1.2 grains of Lil’Gun does not translate into a great deal in the way of velocity, and usually not enough to allow a much heavier bullet. For the record, K-Hornet brass based on a Winchester case held only 14.7 grains of Lil’Gun, placing it closer to a Federal Hornet than a Federal K-Hornet. Such are the challenges of playing with the K-Hornet. For consistency, I did all my testing using Federal K-Hornet brass.

About 15 years ago, I bought a custom .22 K-Hornet rifle. It had a modified BSA Martini action fitted with a Winchester Model 43 barrel. Most sources say the bore on the 43 was .224 inches, but mine slugs at a maximum of .223, with a twist rate of 1:16. The rifle had been built by a reasonably competent gunsmith; the stock was decent but the conversion from rimfire to centerfire was not. The rifle came with a set of RCBS dies marked .22 K-Hornet.

In my innocence, I started with some moderate loads, but did not allow for the difference in case capacity post-1950. I encountered some problems that swiftly escalated into a blown primer, a bolt stuck fast and a trip to a gunsmith. This was the first of five such trips, to four different gunsmiths, over the next 15 years. Nothing worked. Finally, in 2019, I turned the rifle over to single-shot specialist Lee Shaver, who completely rebuilt the centerfire conversion mechanism, and now it’s fine.

The Martini action is very strong, but the lever lacks much in the way of camming power to open the breechblock, and anything from a protruding primer to a stuck firing pin can lock it up. For this reason – and my previous experience with the rifle – I started very low in load development for this article, the purpose of which was to try some new powders in the venerable K-Hornet.

The two traditional powders for both the Hornet and K-Hornet are Alliant’s 2400 and IMR (or Hodgdon) 4227. In fact, 2400 got its name from the fact that it propelled a 50-grain Hornet bullet at 2,400 fps. I tested some loads with those two powders, but added Hodgdon’s CFE BLK and Lil’Gun to see if newer powders could produce a significant improvement.

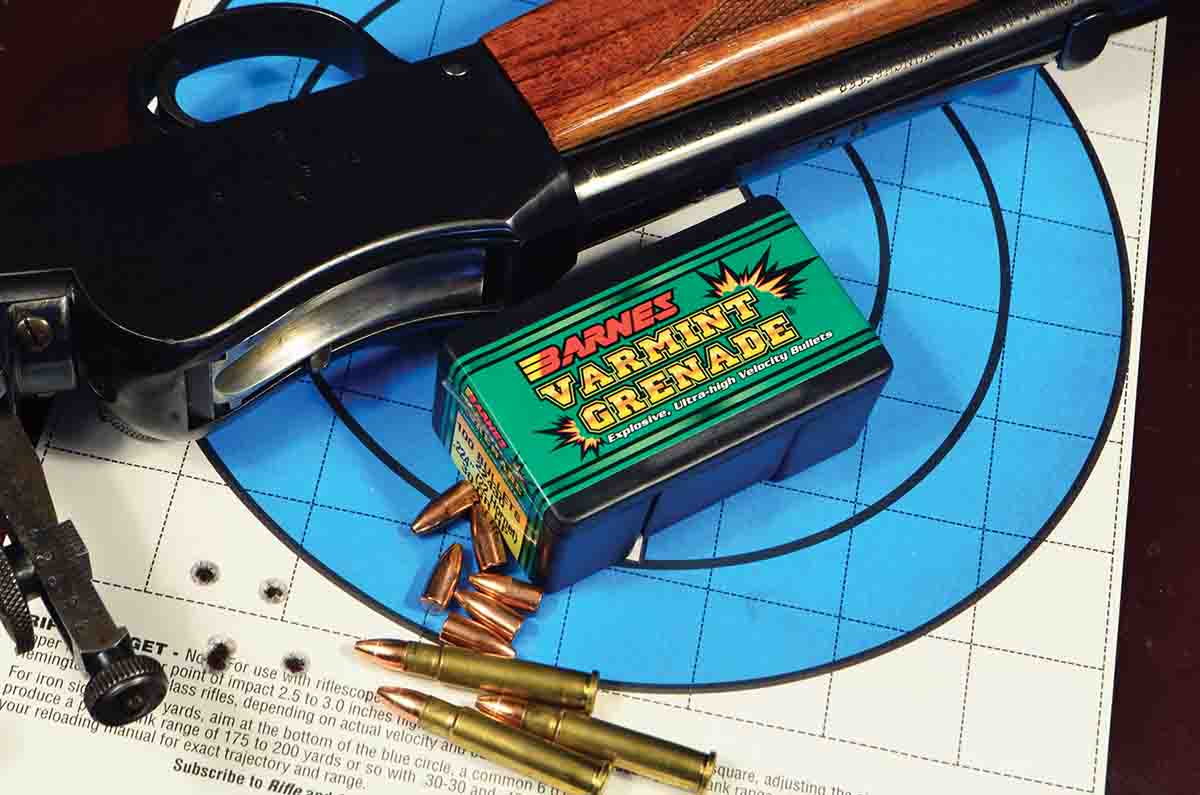

Because of the slow twist rate in my rifle, I limited bullets to 46 grains and less. I had two Sierra bullets, 40- and 45-grain softnose, in .223-inch diameter, made specifically for old Hornets. I also found some Barnes 30-grain Varmint Grenades, Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tips and Speer 46-grain flatnose bullets. These three are all .224 inch.

In theory, it should not make a huge difference in pressure using a .224-inch bullet in a .223-inch bore, but given the other variables involved, it was deemed wise to start at the very low end with everything and work up, watching for any pressure signs. All of the results are given in the accompanying table. Because of a general shortage of components, I did not shoot groups with every combination, only the ones I thought would be most useful.

Completely puzzled, I consulted Ron Reiber, Hodgdon’s longtime (and now retired) ballistician, who advised, (a) the flattened indentations were a sign of low pressure, not high; that (b) the higher velocities could be a result of my supply of Lil’Gun drying out slightly, and (c) that the K-Hornet case would not hold enough Lil’Gun to drive pressures into the danger zone regardless. With that in mind, I moved on to the more adventurous loads seen in the accompanying table.

First of all, I detected absolutely no difference in velocity or pressure signs between .223 and .224 bullets. In this rifle, at least, they appear to be interchangeable.

Second, both CFE BLK and Lil’Gun offer demonstrable improvements in ballistic performance compared to 2400 and IMR-4227, although the latter still do everything they were touted to do a half-century ago.

Third, given the much wider range of bullet weights and styles available today, a K-Hornet (or, for that matter, the original Hornet) is a worthwhile rifle that can be made to do many different things, from outright varmint control to small-game hunting for meat.

Regarding accuracy testing, this rifle is fitted with a Parker- Hale tang (aperture) sight and globe front sight, which are more suited to 50- or 75-yard shooting than to 100 yards. Similarly, the K-Hornet is more likely to be directed at a target 50 to 100 yards away than to 100 or beyond – hence the choice of 50-yard groups.

Of the combinations tried, three gave the best potential results: the Barnes 30-grain Varmint Grenade, with CFE BLK; the 40-grain Sierra (.223) softpoint; and the 46-grain Speer flatnose.

If you want to turn your K-Hornet into a rifle for prairie dogs, crows or rampant garden moles, the 30-grain Barnes offers the ultimate velocity with no pressure problems, combined with excellent accuracy. The table is somewhat misleading, because the 1.64-inch group at the higher velocity was actually .78 inch, with one flyer, so it wins the consistency stakes.

The 40-grain Sierra with Lil’Gun would be a good all-around load, but it’s a wild card; the velocity with Lil’Gun seems to be the result of my powder supply drying out, so it’s not something I can expect to do forever. In fact, that really renders all the results with Lil’Gun questionable. It delivered a four-shot group of .97 inch, with one flyer that expanded it to 1.65.

The Speer 46-grain flatnose is a traditional Hornet bullet for small game, and it is quite accurate as well. It would be a good turkey load, among other things.

The Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tip, alas, is simply too long (.691 inch) to be stabilized by a 1:16 twist, even at velocities approaching 3,200 fps. Various twist-rate calculation programs recommended anything from 1:11 to 1:13.8, so the bullet is simply a non-starter in this rifle.

Some of the loads given on the Hodgdon website, including those for Lil’Gun and CFE BLK, are compressed. Hodgdon used K-Hornet brass reformed from Winchester, which my tests showed has less capacity than Federal brass, yet I found some of Hodgdon’s maximum loads impossible even to get into my cases. Not knowing what vintage its Winchester brass was – or, for that matter, its chamber dimensions compared to mine – it’s impossible to say what this all means except it’s one more good reason, when working with the .22 K-Hornet, to start very low and proceed very carefully, reading the fine print all the way.

Still, that’s part of the fun of handloading, and the K-Hornet remains a useful, if troublesome, cartridge at the age of 80 years and counting.

.jpg)