6.5 Millimeters of Magic

Outperforming Since Bismarck

feature By: Terry Wieland | April, 26

It is impossible, 140 years later, to say exactly who first concluded that a bullet of 6.5mm diameter, .264 in imperial measure, was the perfect caliber for a rifle.

It is also almost impossible to explain why it took Americans so long to agree. By 1905, 6.5mm cartridges were standard at every level in Europe; not until a century later, in 2007, did a 6.5mm rifle conquer the American heart and become the rifle everyone wanted.

Why, you ask? There were many reasons, some legitimate, some barely credible. All we can do now is be grateful we’ve come to our senses.

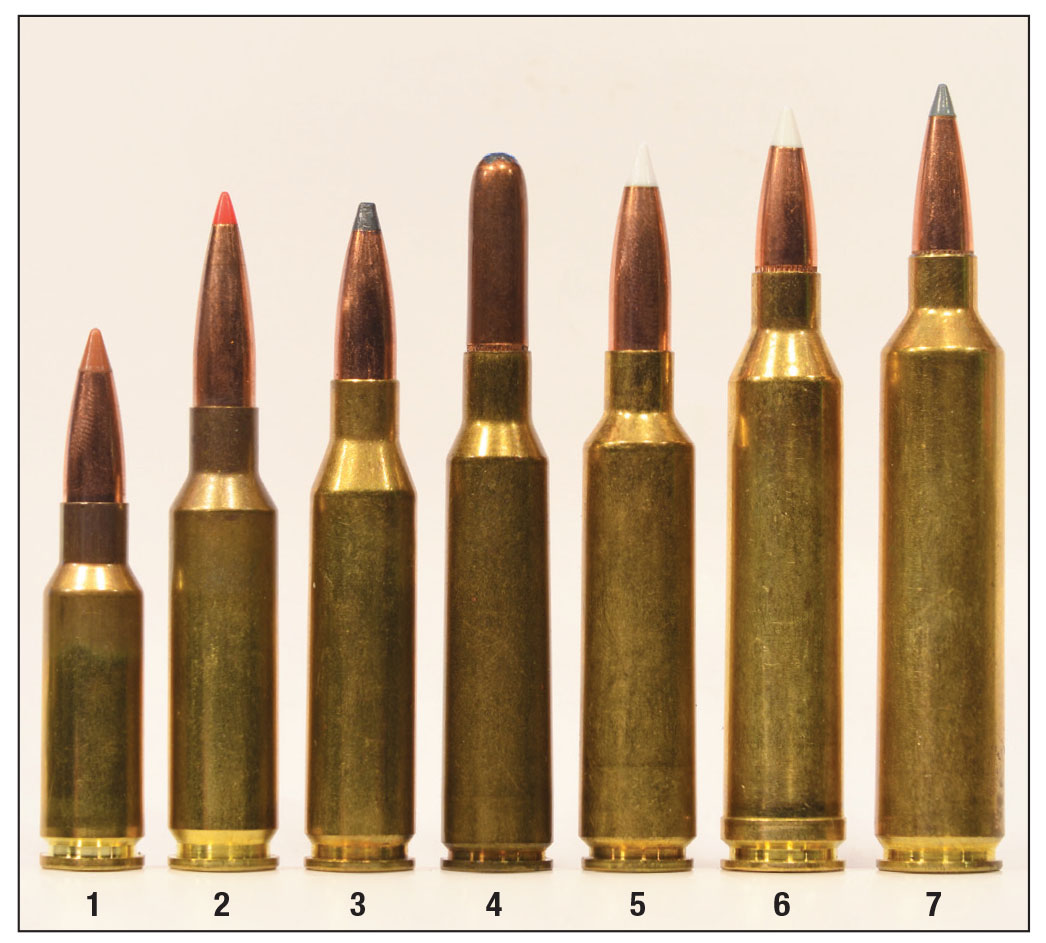

Among the 6.5s designed or inspired by Mannlicher were the 6.5x53R, shared by the Dutch and Romanians, 6.5x52 (Italian), and, most famous, 6.5x54 Greek, which became the civilian 6.5x54 Mannlicher-Schönauer.

Not to be outdone, Mauser developed the 6.5x55 for the Swedes, Japan designed the 6.5x50 Arisaka, and France the 6.5x53.5 Daudeteau. Portugal had the 6.5x58 Vergueiro for a rifle that was a Mauser-Mannlicher hybrid. On the civilian front, Germany had a 6.5x57 (the 7x57 necked down), 6.5x54 Mauser (for its Kurz action), and a variety of earlier straight-wall 6.5mm target cartridges similar in shape to the American 32-40.

This performance, modest by modern standards or even by the standards of 1910, was in fact the key to the 6.5’s success: A long, strongly constructed, heavy-for-caliber bullet at a reasonable velocity would penetrate deeply every time and kill out of all proportion. It was also easy to shoot accurately and not overly loud.

For these reasons, and against all the odds, Mannlicher’s Model 1903 with its 6.5x54 cartridge and 156-grain bullet at 2,461 fps became a favorite for hunting elephants, Cape buffalo, and Alaska brown bears and grizzlies. These are documented cases by famous hunters: W.D.M. (Karamoja) Bell and Werner von Alvensleben in Africa, and Charles Sheldon and Annie Alexander in Alaska.

Published accounts from the time rarely give details of rifles and specific ammunition used, or cartridge nomenclature, so there is a certain amount of piecing together when it comes to reporting exactly what Sheldon used to hunt Dall sheep and kill grizzly bears, and the same goes for Annie Alexander during her zoological expeditions on Montague Island. There is enough detail, however, to report with some certainty that the rifles were European, and fired long, heavy 6.5mm bullets.

British gunmakers were eager to get in on the business. George Gibbs, of 505 Gibbs fame, introduced a cartridge called the 256 Gibbs Magnum. It was not a roaring success, but it did establish the confusion based on nomenclature that later clouded the 6.5’s path to glory. The 6.5’s groove diameter is .264 inches, while its bore diameter is .256. Hence, the Gibbs, since the Brits usually adhered to the bore diameter.

The United States at this time was largely loyal to .30 and .32 caliber cartridges. When Savage introduced the 250-3000 in 1915, designed by Charles Newton and the first American factory cartridge to break the 3,000 fps barrier, a sea change occurred in two ways. First, 3,000 fps became practically a holy grail for cartridge designers, and second, the quarter inch (.257) cartridge became the darling of the day.

When Newton introduced his most famous cartridge in 1913 – a 6.5mm – he called it the 256 Newton instead of what should have been, by American lights, the 264 Newton. Was he adhering to English custom? Or paying homage to the .257? Whichever it was, it did the 6.5mm no favors in its quest for American hearts.

A decade later, when Winchester decided it needed a small-caliber, high-velocity cartridge to outshine the 250-3000, it ignored the obvious solution, the 6.5mm, and came up with something totally new: the 270 Winchester. It changed the American hunting world, and its influence was felt for the next 50 years.

In retrospect, it makes sense. For Winchester to neck the 30-06 down to 6.5mm would have almost exactly duplicated the 256 Newton, which they did not want to do, and a 25-06, wonderful as the cartridge later proved to be, would not have allowed a heavy enough bullet for Winchester’s purposes. Hence, the 270. From that point on, the 6.5mm in its various forms was running a losing race.

All of which is not to say the 6.5 was totally lost. The 6.5-06 gained adherents as a fairly prosperous wildcat, and even achieved temporary respectability when A-Square started loading it as a factory cartridge in the 1990s, but let’s leave wildcats and semi-wildcats out of this.

Then, some bright light got the idea of chambering it in Winchester’s immensely popular Model 70 Feather-weight, a 6.75-pound rifle with a 22-inch barrel. This may be the single dumbest decision in the history of American riflemaking and was obviously a call by marketing guys who did not hunt, shoot, or even read about ballistics. The result was a creation that deafened you and kicked you out from under your hat, all the while delivering poorer ballistic performance than a 270. The disappearance of this misbegotten critter was one of the (few) positives of Winchester’s redesign of the Model 70 in 1964, but the 264’s reputation was tainted from then on.

Not to be outdone, it seems, Remington tried its own 6.5mm in 1965, a short-short magnum based on the belted 375 H&H case. They shoehorned it into the short Model 600 bolt action, and fitted it with, first, an 18.5-inch barrel, and later a 20-inch barrel. Although the 6.5 Remington Magnum case has about the same capacity as a 30-06, the rifle’s short magazine precluded loading any long, heavy bullet without encroaching on powder space so much it severely limited what performance was left after those short barrels had done their worst.

In rifles with appropriately long actions, magazines and barrels, both the 264 Winchester Magnum and 6.5 Remington Magnum are fine cartridges, but they were hamstrung by their parent companies.

Parker-Hale imported some beautiful bolt actions built on the Spanish Santa Barbara action, and I acquired one in 1987, largely by accident. I wanted a 270 Winchester, but they were out of stock. I then embarked on an adventure of learning just how good a 6.5 of the old school could be – 140-grain bullet, 2,780 fps from a 22-inch barrel and a .308-inch three-shot group at 100 yards. I can’t publish the load, since it exceeds standard data, but I took that rifle to Alaska in 1990 and killed a lovely Dall ram with it.

Well, some were. Unfortunately, they were mostly that band of intrepid iconoclasts who play with wildcats and having been sold too many bills of goods over the years about the performance of somebody’s brainchild, editors weren’t interested in those, either. So the 6.5 in various forms hung around on the outside, looking in.

If one wanted to isolate the specific problems that held the 6.5mm back, they were roughly these: First, its great virtue is its long-for-caliber bullet giving great penetration, but requiring a very fast rifling twist. Early American designs tried to make it a high-velocity number, but that’s not where its strength lies.

Second, to get optimum ballistic performance, you need the right magazine length to allow the bullet to be seated out where it should be, combined with the right chamber length and proper rifling twist to stabilize those long bullets. The big riflemakers were not willing to make those allowances, and insisted that merely rechambering an existing design was enough. It rarely was.

Third, suitable bullets were rare. To the best of my knowledge, the only American company that made a heavy 6.5mm 50 years ago was Barnes, with a 160-grain. For everyone else, 140 grains was as high as it went. In Alaska, I used a 140-grain Nosler Partition, one of the best hunting bullets ever made, and it’s what I would use if I went hunting today with that Parker-Hale. (Alas, I no longer have it.)

In fact, the Creedmoor is not quite as powerful as the ill-fated 6.5-08 A-Square or 260 Remington (same cartridge) that came along in the mid-1990s and it was based on a 40-year-old wildcat. Yet again, Remington misfired with a good cartridge, but there’s no room to go into that now. I had one, found it wanting, and traded it for a really nice, restored Ithaca trap gun.

Since the Creedmoor broke the ice, a plethora of new and newish 6.5s have come along, from the 6.5 Grendel on the modest side to the 26 Nosler and 6.5-300 Weatherby on the outlandish. In between, we have the 6.5 PRC – roughly equivalent to the old 6.5-06 wildcat.

Obviously, the great gains for the 6.5mm have not been in the realm of new or radical case design, or even advances in bullets (although there have been many).

The new 6.5s shine because they have shed all the old baggage that held the others back, such as, in the case of 6.5x55, limitations on allowable pressure because of the perceived weakness of the Swedish Mauser. New rifles have sufficient freebore to accommodate long-for-caliber bullets, allowing optimum seating depth for both accuracy and powder capacity. They have tight rifling twists that will stabilize a bullet as long as a torpedo.

Not one single bit of this is new. What is new is combining all the right factors in a rifle and cartridge that can really outperform. The 6.5s are like a racehorse that has finally been given the right feed, a good set of shoes, and room to run.

.jpg)