Hunting Loads for the 30-30 Winchester

Bringing a Venerable Cartridge up to Speed with Modern Bullets

feature By: Patrick Meitin | April, 26

In an industry that has given us the 350 Legend, 360 Buckhammer and 400 Legend, there is really little need for the ancient 30-30 Winchester in today’s deer woods. Like the venerable 300 Savage, 35 Remington and 45-70 Government, the 30-30 Winchester persists because there are so darn many rifles chambered for them still floating around (7-plus million Winchester Model 94s alone, by some estimates). Also, because they have worked just fine for several generations of deer, wild hog and black bear hunters who hold to an “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” attitude. This says nothing of the nostalgia factor…

It could also be argued that modern ammunition has rendered the 30-30 Winchester more potent than ever.

Introduced in 1895, the 30-30 ushered in the age of smokeless powder. The 30-30 Winchester really should have reached its expiration date long ago. Yet you’ll still find the cartridge chambered in a wide variety of quality rifles, usually fast-handling and handy carbines ideal for the 80- to 125-yard treestand or still-hunting whitetail pursuits the vast majority of American big-game hunters practice. Most of these rifles are lever-actions, though some 30-30 chambered bolt guns (Savage Arms) and single shots (Harrington & Richardson and Henry) are certainly in circulation.

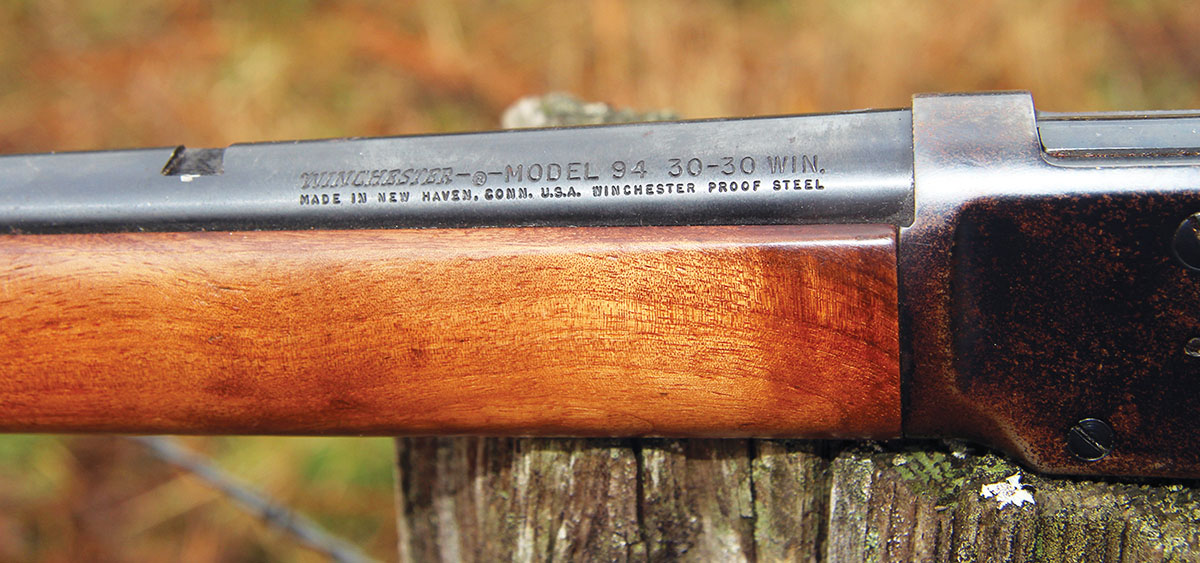

The Model 94 was produced by Winchester Repeating Arms Company from 1894 to 1980, then by U.S. Repeating Arms under the Winchester brand until 2006. Since 2010, Model 94s have been manufactured by the Japanese Miroku Corporation and imported by Browning Arms Company. Later models include tang safeties.

According to its serial number, my Winchester Model 94 was manufactured around 1982, early enough not to include the angle-eject upgrade that allowed optics mounting. This top-eject lever gun was previously used as a Cowboy Action rifle, so it has seen plenty of use. It was equipped with a rear Williams aperture sight and a bright fiber optic front bead. The steel action bluing shows considerable wear, though the rifle is in perfect working order and the stock is in great shape. The rifle features a 20-inch blued barrel with 1:12 rifling twist and a sporter-weight contour. Overall length is 38 inches. The black walnut buttstock includes a classic straight grip and shotgun-style hard plastic buttplate (instead of the blued steel carbine strap buttplate advertised on newer models), with 11⁄4-inch drop at the comb, 13⁄4-inch drop at the heel, and 131⁄2-inch length of pull. The black walnut forearm is classic Model 94, barrel band and all. There is no checkering or sling swivel studs.

Many of the features listed for present 94s are absent from my rifle, including the aforementioned steel buttplate, radiused lever edges, drilled/tapped hammer to accept a spur extension and scope-base taps. Winchester’s website lists 6 pounds, 8 ounces for weight; my rifle correlates closely at 6.12 pounds. The rifle is loaded via the steel side gate, and the full-length tubular magazine holds seven rounds. To replace this rifle today would set you back around $1,325, making it considerably more costly than a base-model bolt-action rifle such as a Mossberg Patriot, Savage Axis or Ruger American.

The 30-30 Winchester has long been loaded with lead-core bullets weighing 150 or 170 grains. The 150-grain bullets can be driven to 2,300 feet per second (fps) with maximum loads, and the 170-grain bullets up to about 2,200 fps. SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute) Shooting Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) runs about 42,000 pounds per square inch (psi)/38,000 copper units of pressure (CUP). These have remained 30-30 standards for more than a century.

One easy way to modernize the 30-30 Winchester is through the introduction of nontoxic monolithic copper bullets. This, not incidentally, also makes the old cartridge legal in the People’s Republic of California and its state-wide ban on all lead projectiles. These rules also apply to select federal wildlife management areas across the country where deer hunting is permitted. California’s lead ban started in designated Condor Zones on the premise that the endangered species were ingesting lead fragments from shot game and becoming sick or dying. Almost predictably, the lead ban eventually applied to the entire state. In their effort to make shooting more inconvenient and costly, California lawmakers may have actually done the 30-30 owner a favor, as there are ballistic advantages to be found in lead-free bullets.

Copper is obviously lighter than lead, the latter 27 percent heavier than the same volume of copper. This typically means that copper bullets are longer than the same-weight lead-core projectiles, generally boosting ballistic coefficients. It also means that a copper bullet with the same profile as a lead-core bullet weighs less, resulting in higher muzzle velocities. There is also the matter of copper’s controlled-expansion properties, the reason Randy Brooks of Barnes Bullets conceived the approach with original Barnes X bullets. In short, this means a monolithic copper slug of a particular weight exhibits the same energy delivery and penetration potential as a lead-core bullet weighing about 20 percent more, generally speaking. A 140-grain copper bullet, for instance, behaves more like a 170-grain lead-core bullet. More speed, less drop, superior terminal performance and greater reliability around bone. These are all net positives, especially for a relatively moderate cartridge such as the 30-30 Winchester.

The tubular magazine of the average 30-30 Winchester lever rifle, of course, requires flatnose or roundnose bullets (Savage’s Model 99 rotarymagazine a standout exception). This prevents potential primer detonation under recoil caused by a sharp point, which would destroy the rifle and possibly injure the shooter. In copper, standard flat or round noses are replaced by a large hollowpoint that essentially encircles the primer pocket, or by Hornady’s MonoFlex “pencil eraser” polymer tip, which also provides superior aerodynamics.

After extensive searching, an endless array of nontoxic bullet options for the 30-30 Winchester did not appear. The best 30-30-ready copper bullets discovered include Cutting Edge Bullets’ 135-grain Raptor 30-30 Version 2 (Cutting Edge also offers 100- to 145-grain brass ESP Raptors, Lehigh Defense’s 140-grain Controlled Chaos, Hornady’s 140-grain MonoFlex, Hammer Bullets’ 143-grain Lever Shock Hammer (they also offer a 120-grain Lever Stone Hammer) and Barnes’ 150-grain TSX FN FB. There may be others, but these are what I was able to discover. Unfortunately, I could not secure the 135-grain Cutting Edge example, which still leaves us with a solid four-bullet lineup ideal for big-game hunting.

New Starline cases were squared up at 2.029 inches and full-length sized to ensure proper functioning in the lever-action, which does not provide the camming action of a bolt rifle going into battery or during extraction. The tubular magazine necessitates crimping bullets into place, which also requires trimming all cases to a uniform length to ensure consistency. I also added a generous inside chamfer to promote smooth seating past the mono-copper pressure-relief grooves, as 30-30 cases aren’t particularly robust, making them prone to crumpling under pressure. Seating depths were determined by each bullet’s provided crimp groove or cannelure. Seating was conducted in one step, returning to apply the crimp in a separate operation. In fact, having several 30-30 die sets on hand, I removed the seating stem from an extra seating die to be dedicated to that task, saving a little time at the bench. Winchester WLR primers were used for all loads.

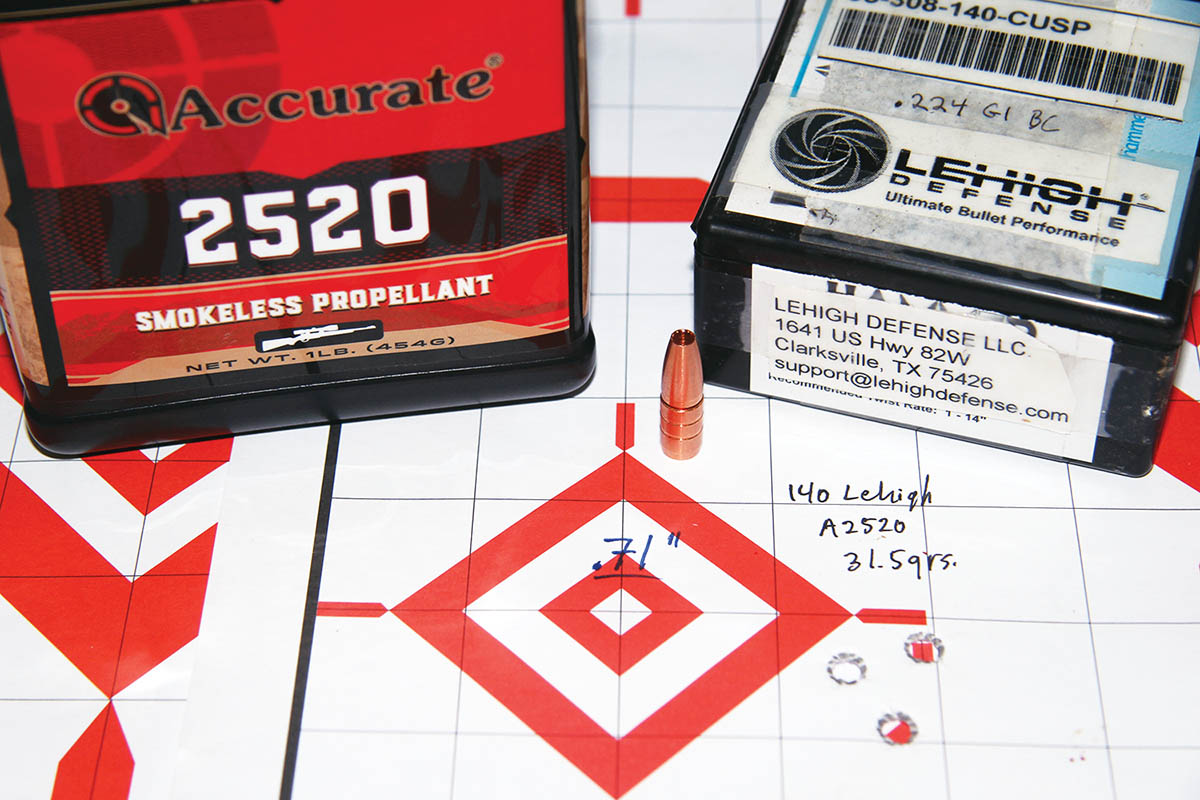

Many classic powders prove compatible with the 30-30 Winchester, such as Winchester 748, Hodgdon 335 and BL-C(2), IMR-4064 and Alliant Reloder 15, among them. Going with the modern theme of the nontoxic bullets, I strived to introduce as many newer, temperature-stable, cleaner-burning powders as possible. The powders chosen fell between Hodgdon 322, with a relative burn rate of 85, and Hodgdon LEVERevolution, with a relative burn rate of 121. Also auditioned were Accurate 2230, A-4064 and A-2520, Ramshot TAC, Alliant Power Pro Varmint, Hodgdon Benchmark, Vihtavuori N135 and N140, Shooters World Match Rifle (with similar characteristics to A-2520) and Winchester StaBALL Match. The Hodgdon examples are Extreme Extruded powders, including excellent temperature stability. The Vihtavuori powders are temperature-stable and include a copper erasing ingredient, just like the Winchester StaBALL powders. The others make no specific claims regarding temperature stability or copper-erasing ingredients.

The Lehigh Defense Controlled Chaos is a 140-grain hollow point measuring 1.085 inches long and including an approximately .135-inch wide by .50-inch deep hollow point cavity. It holds three pressure-relief grooves, the uppermost cut acting as a crimping groove in addition to initiating fracturing during penetration. It sports the slightest boat-tail, giving it a .224 G1 ballistic coefficient (BC). It will expand down to 1,500 fps, which gives it a 225-yard maximum range from the 30-30 Winchester. With a 100-yard zero, sent at about 2,300 fps, this bullet drops 7.8 inches at 200 yards.

The 140-grain MonoFlex by Hornady measures 1.205 inches long due to a pronounced boat-tail and red Flex Tip. The design provides the flattest trajectories possible from the 30-30 Winchester, while also ensuring 95 percent weight retention and reliable expansion at a bit more than 300 yards from the 30-30 Winchester. The MonoFlex’s .295 G1 BC means just 7 inches of drop at 200 yards with a 100-yard zero and when sent at about 2,300 fps. The MonoFlex includes two pressure relief grooves, the top groove used for crimping. A long lower bearing surface prompted me to dial powder charges down a touch to avoid sticky cases.

Hammer Bullets’ 143-grain Lever Shock Hammer was designed specifically for tube-feed lever rifles. They are 1.053 inches long and require a minimum 1:14 rifling twist. They sport an approximately .113-inch wide by .42-inch deep hollowpoint cavity. Five “hourglass” body grooves allow using standard load data for like-weight bullets, and the uppermost groove was used for crimping. They include an estimated .287 G1 BC, which means that when zeroed at 100 yards and sent at about 2,300 fps, they drop 7.1 inches at 200 yards.

Barnes’ 150-grain TSX FN FB translates to Triple-Shock X, flatnose, flatbase. They are 1.082 inches long and include an aggressive .12-inch wide by .52-inch deep hollow point opening for ensured expansion at slower velocities. These dimensions also explain the relatively short length-to-weight ratio of this bullet. The TSX includes four pressure relief grooves, the uppermost cut used as a crimping groove. With a .184 G1 BC and launched at around 2,250 fps, this bullet drops 9.1 inches at 200 yards.

As a precision-minded shooter who spends more time behind varmint rifles sniping burrowing rodents than big game, and as someone who admittedly hasn’t shot an iron-sighted rifle extensively in decades, I didn’t expect to be wowed by the results of this test. To be completely honest, the only 30-30 rounds I’ve ever shot a considerable sum have been fired from the 10-inch barrel of a scoped Thompson/Center Contender. Which also means I’ve never crimped a 30-30 round.

Shooting distance was pondered at length, as I desired comprehensive groups and not overlapping, vital-sized patterns on paper. As a compromise, 50 yards was decided upon, which says as much about my faith in lever-gun accuracy as it does my confidence in shooting iron sights. This was also easy to rationalize, as in the thick whitetail habitats of northern Idaho or mesquite/prickly-pear hog haunts of Texas, where I’m most likely to utilize this rifle, 50 yards represents typical shooting range, whether still-hunting or occupying a treestand. Ultimately, these apprehensions proved completely unwarranted; the rifle shot far better than expected.

.jpg)