Propellant Profiles

Vihtavuori N150

column By: Rob Behr | April, 26

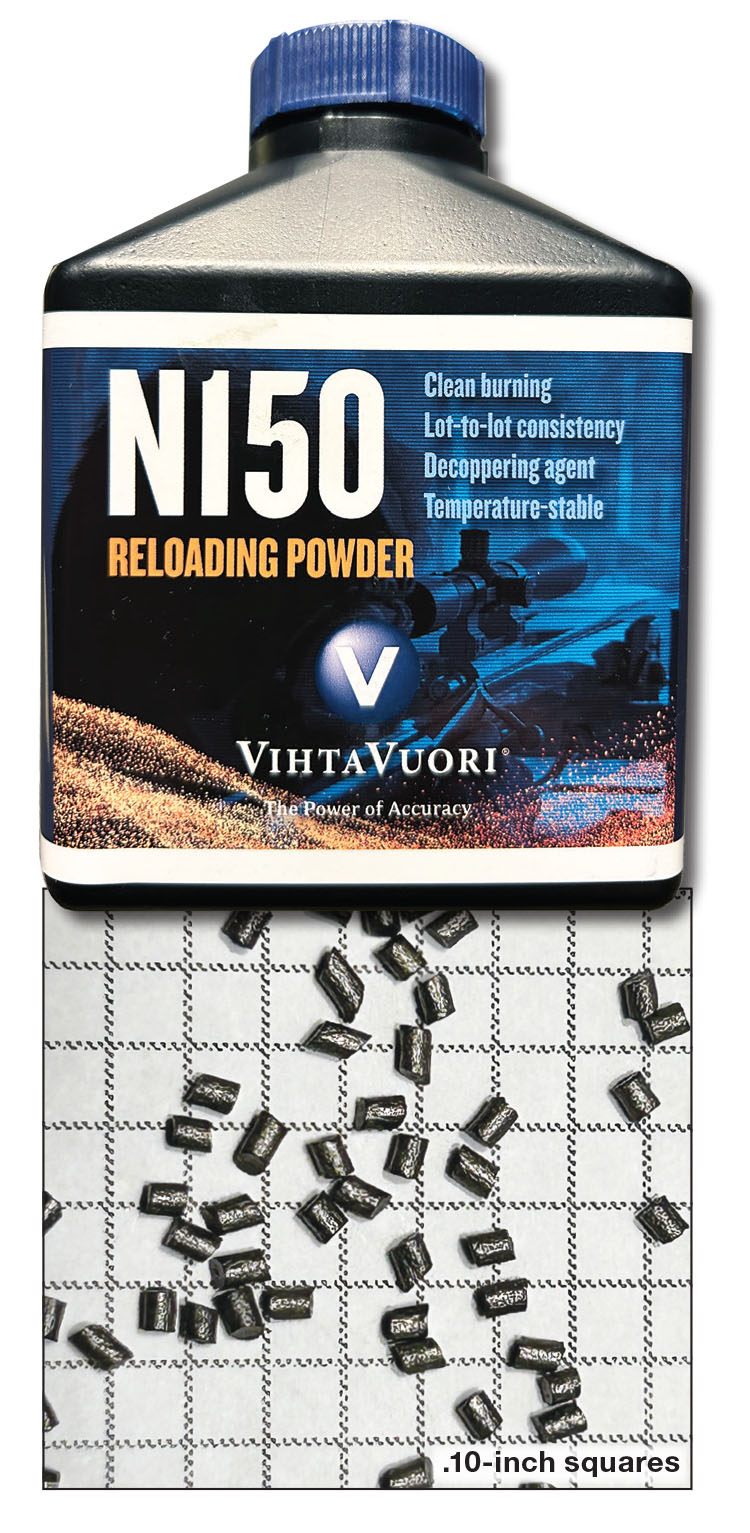

With a burn rate that is close to IMR-4350, and a grain that measures .037 inch in diameter and an average of .047 inch in length, N150 had filled the 308 Winchester cases almost completely. The Barnes 150-grain TTSX bullets had made noticeable crunching sounds as they were seated. These were heavily compressed loads.

Physical Characteristics

Vihtavuori N150 is a tubular, single-based propellant that uses a proprietary anti-coppering agent to reduce fouling. The black grains, modestly longer than they are thick, are light reflective and glisten in a powder hopper. With a bulk density of .910g/cc, the powder meters well and is resistant to static electric cling. There are modest variations in length, but overall, the powder’s appearance is uniform.

Temperature Stability Testing

Because I had intended to test for accuracy using the 308 Winchester, I elected to freeze another batch of laboriously prepped cartridges overnight in a chest freezer, right next to part of my wife’s recently harvested moose’s hide, which she swears she is going to tan. I wouldn’t bet the farm on that one, Dear Reader.

Shooting conditions were good the morning of testing, with light crossing winds and a temperature of 32 degrees Fahrenheit. The thermometer in my insulated container was steady at -22 degrees Fahrenheit. Shooting slowly to allow for at least some chamber cooling between shots produced an average velocity of 2,613 fps from my 308. The cartridges that had been maintained at 70 degrees Fahrenheit averaged 2,663 fps.

The warmer cartridges managed a very respectable 9 fps extreme spread, while the frozen ones had shown a broader than expected extreme spread of 41 fps and an average velocity decrease of 50 fps. There is, however, a broader picture that needs to be considered here.

One of my favorite college professors liked to joke that statistics is more of an art than a science. Considering he was a statistician, I tend to agree with him. Testing like this, based on small samples, can produce misleading results that might be altered by simply adding more data points. Nonetheless, in this sample, testing showed the frozen ammunition produced a 1.88 percent decrease in velocity. This is still a modest shift considering that the sampled temperature range was approximately 92 degrees Fahrenheit.

Powder Positional Testing

Powder migration within a cartridge can cause surprisingly high variations in pressure. Ballistic lab testing procedures recognize this and go to great pains to orient the powder, as much as possible, toward the primer. This position creates the highest pressure values for a given powder/bullet combination. The lowest pressures are created when the propellant is oriented near or against the bullet. This is why charges that fill the case to the base of the bullet, or are slightly compressed, are more likely to have lower extreme velocity shifts. They do not allow powder migration within the cartridge.

Vihtavuori’s load data provided an interesting load combination for the 25-06 Remington. The 25-06 has approximately 66 grains of water capacity. Vihtavuori’s combination called for a maximum charge of only 35.8 grains of N150 behind a 120-grain Speer Spitzer bullet. Because the case was so under filled, I chose it for positional testing.

Testing with the powder oriented toward the bullet, a condition produced by a good deal of bullet-down shaking, and loading the rifle in a muzzle-down orientation, I chose a target with a slightly downward trajectory and repeated this test for eight more shots. The resulting velocity was 2,554 fps. With the powder oriented toward the primer, the result averaged 2,573. This difference of 19 fps, a shift of .74 percent, is impressively small considering how much room there was for powder migration within the cartridge. This load, probably intended for recoil-sensitive shooters, would be a blessing in the field.

Fouling Cleanup

My 25-06 Remington is built on a Mauser K98 action with a good-quality Colt Sauer barrel. Because it was to be used as a testbed for fouling, I carefully cleaned this lovely but neglected rifle. It had come to me from a friend who had purchased it from another friend. Apparently, all three of us had never cleaned that poor, neglected rifle. Thanks to Montana Xtreme Copper Killer and a lot of patches, the rifle went to the range with a clean bore. It was a long and malodorous task.

Thirty-six rounds are not a lot of shooting, but it is enough to give a feeling for the fouling potential of a propellant. I was especially interested in N150’s anti-coppering agent and the impact it would have on my laboriously achieved copper-free barrel.

The first dry patches produced a dry gray residue with no partially burned powder granules. The patches wetted with Montana Xtreme Bore Solvent produced dark powder fouling that faded to nothing after the fifth patch. Copper Killer failed to produce a trace of copper fouling, even after the third patch. It appears that Vihtavuori N150 is as good as the company’s advertising suggests. It is clean burning and the de-coppering agent is effective.

The Takeaway

Vihtavuori has long been seen as a fine quality propellant on the American market, with an admirable reputation among the benchrest community. It was also more costly than its American competitors. Times have changed that equation. American propellant prices have skyrocketed over the last few years while Vihtavuori’s prices have remained relatively constant. In my hometown, the Vihtavuori products are priced comparably to popular American brands. Now that they represent both value and quality, perhaps it may be time to give Vihtavuori a chance as your next go-to powder brand.

.jpg)