Handloading for NRL Hunter

Where Precision Reloading Meets Hunting

feature By: Alan J. Garbers | April, 26

As a handloader, my options are dictated by the required power factor. A competitor’s loads must meet a power factor of 380,000, which is calculated by multiplying the bullet weight by the muzzle velocity. In its most basic form, the shooter must use a cartridge powerful enough to achieve power factor while keeping the recoil low enough to keep a good sight picture to see impacts. On the flip side, a shooter must develop a precision mindset. Protocol demands that each case, bullet, powder and primer come from the same manufacturer, same lot and be loaded the same every time. Many competitors go so far as to buy enough cases, bullets, powder and primers from the same lot to last the life of the barrel. Depending on the cartridge, that may be as few as 1,500 or as many as 5,000 shots.

Finding cases can be frustrating, but manufacturers are catching up with demand. I used to buy whatever I could find, but after bad experiences with soft primer pockets, I became more demanding. Since then, I limit myself to ADG, Peterson and Lapua. They take extra steps to harden the case base, which reduces primer pocket stretching.

Chamfer the Case Mouth: This is for new brass and cases that have been trimmed.

De-prime: I use Lee’s universal de-priming die to eject the spent primer. The die does nothing else, and no contact is made with the actual case. I do this first so that the primer pockets are exposed for cleaning.

Clean: Sizing dies can be damaged by dirt on used brass. Grit can become embedded in the die surface, causing scoring on each case, shortening its life, or destroying it outright. When I first started cleaning my brass, I used an inexpensive vibratory cleaner filled with Lyman-treated cob grit. It was a noisy, dusty job, and afterwards there was the task of clearing the cob grit from the primer flash holes. A few years ago, I decided to go to a water-and-stainless-steel pin cleaning. The brass looked fantastic, so I donated my vibratory hopper and cob grit to a local shooting club. I was in ignorant bliss.

A few weeks ago, another precision handloader warned me that the stainless steel pins might be peening a lip on the case necks. My smile vanished as I pulled case after case and ran a small screwdriver over the lip. Every one of them indeed had a lip! I am now back to vibratory cleaning with cob grit.

Anneal: Forty years ago, annealing wasn’t listed in any reloading manual; now it is one of the most essential steps in maintaining brass life and precision. As brass cases are used over and over, the brass work hardens, the neck tension changes and eventually cracks. Imagine bending a piece of sheet metal back and forth until it cracks. That’s work hardening. Some shooters anneal their cases after a predetermined number of firings based on their experience. Other shooters anneal after each firing. By not annealing after each use, I have no way to determine how much each piece of brass has changed in hardness and neck tension. If I anneal each time, I know the brass hardness has been reset to zero, and is essentially a new case. To ease my anxiety, I anneal after each firing.

As my budget allowed, I upgraded to an AGS annealer. The process is basically the same, but the timing and temperature remain the same for each case. Other brands do the same thing in a slightly different way.

For those with a larger budget, there are induction annealers. The brass case is briefly inserted into an induction coil. The induction coil induces heat into the case, annealing it. The process is exact. AMP Annealing, or Annealing Made Perfect, is the leader in this type of annealer.

Lubricate: Most competitors I spoke with use Hornady One-Shot Gun Cleaner and Lube. Some prefer Imperial sizing wax. Rusty makes his own spray lube by mixing lanolin oil with 99% alcohol at a 1:15 ratio.

Full-Length Sizing: Every competitive shooter I know bumps the shoulder back 0.002 to 0.003 inch while full-length sizing. I remove the neck-sizing ball from the die and neck-size later. If the primer wasn’t removed previously, it is now.

Neck Sizing: Some prefer outside sizers, others prefer inside mandrels. I like an inside neck mandrel 0.001 to 0.002 inch smaller than the bullet I’m using. For years, I didn’t use lubrication, but then I spoke with another shooter who claimed he saw a change in the shoulder bump when not using lubrication. After sighing heavily, I decided to check myself. I found a change of 0.0005 to 0.0015 inch difference when not lubricated, and I could feel the resistance through the press lever! I found no change in the shoulder bump after lubricating the neck. Case closed.

Check Case Length: If cases are close to or exceed the maximum overall length, trim the lot and chamfer again.

Clean the Brass: Case lube can attract dirt and impair the cartridge’s grip on the chamber walls, leading to false signs of over-pressurization.

Prime: Many shooters want their primers 0.003 to 0.005 inch below the case head. Some shooters prefer standard primers while others spend extra for match-grade primers.

Weigh the Powder: Some experienced shooters forgo weighing every charge and use an old-school volume powder thrower. They adjust the thrower until an average of ten throws gives them the weight they want, then lock it down and get to work. They do check the thrower periodically to ensure it’s still on point.

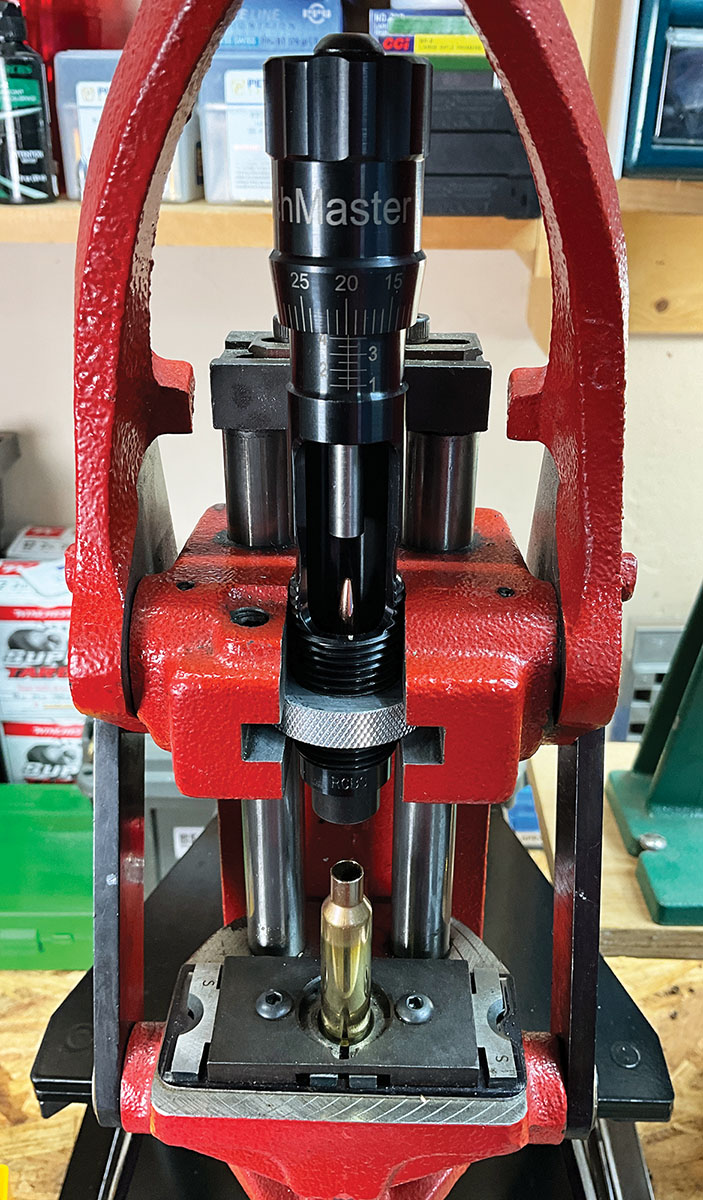

Most electronic powder dispensers are accurate down to 0.1 grains, plus or minus 0.1 grains. The next step up in accuracy is the RCBS MatchMaster. It is precise down to 0.01 grains. The more consistent the powder weight is, the tighter the standard deviation, and the less vertical stringing will occur.

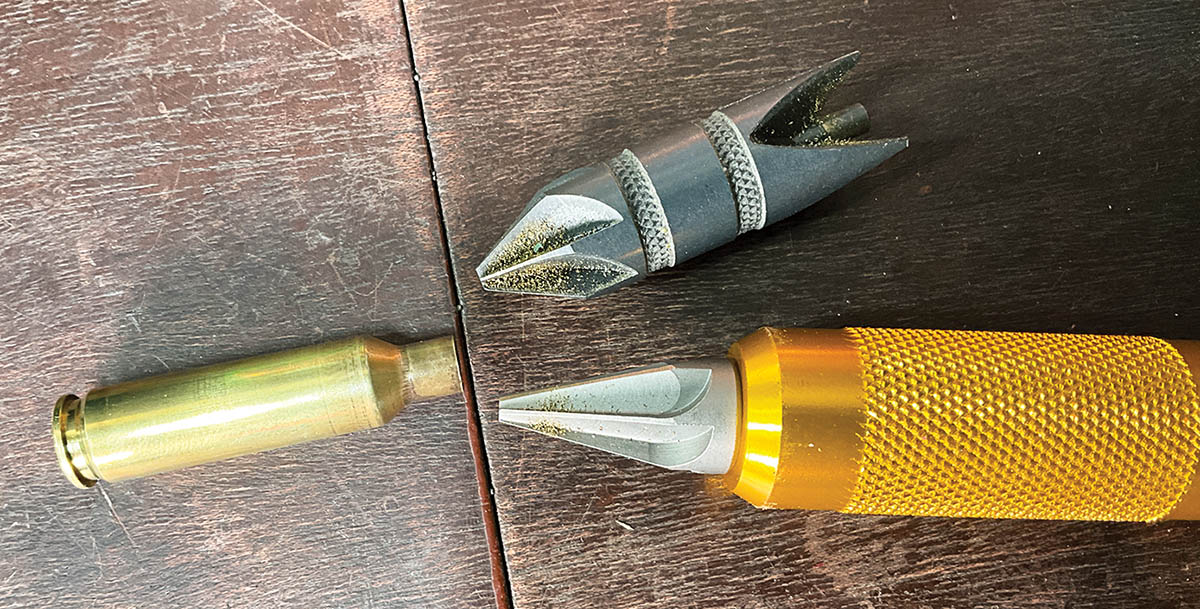

Bullet Seating: Choosing the correct seating stem can make a world of difference. I was in a run of seating bullets, and I kept feeling the bullet stick. I didn’t see anything wrong, but when I checked the

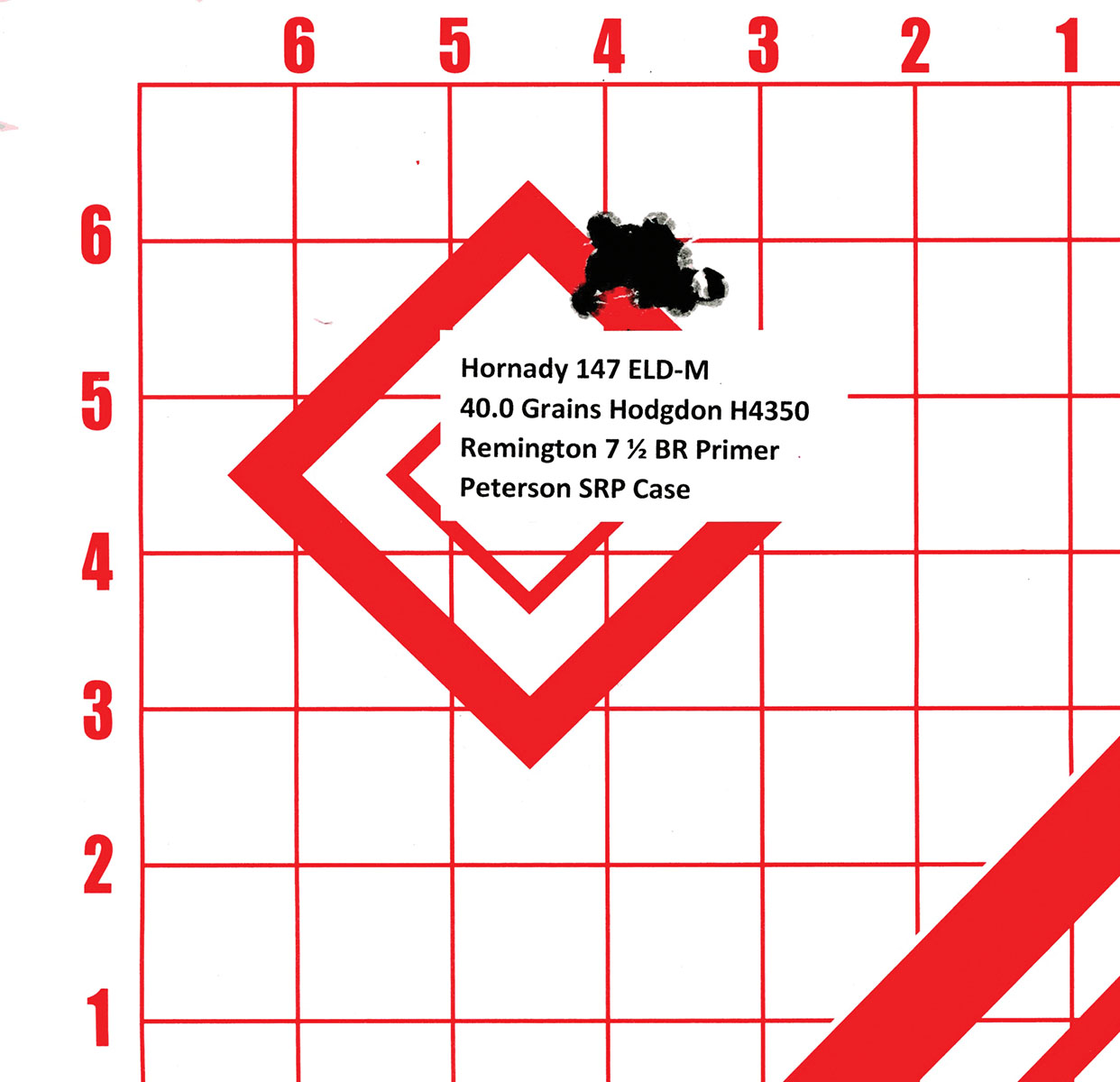

My testing included multiple bullet and powder combinations to find an accurate load that exceeded power factor by a safe margin while minimizing recoil. That’s a tall order. It was always in the back of my mind that my testing was done at 4,900 feet in elevation, which skewed my velocity higher than it would be at a lower elevation, so I made sure my final loads were a safe margin above power factor.

The bullets used included: Berger 135-grain Classic Hunter, Berger 140-grain Elite Hunter, Hornady 140-grain ELD-M, Hornady 147-grain ELD-M, Sierra 150-grain Matchking, Hornady 153-grain A-Tip and the Berger 156-grain Elite Hunter.

The powders tested were: Winchester’s StaBALL 6.5 and 760, Hodgdon’s Varget, Superformance, H-4350 and H-4831, Ramshot’s Hunter and Vihtavuori’s N555 and N565.

You may wonder why some riflecases are offered with small rifleprimer pockets when they traditionally used large rifle primers. For the last few years, I thought it was because of the large rifle primer drought. But when I started digging into it, I found that the small rifle primer cases had been around long before COVID decimated our supply chain. One reason is that since the primer pocket is smaller, the case head is stronger. Some shooters claim to get 20 loadings! Another reason is that the small rifle primer has less brisance, thus the powder ignition is less violent. Some long-distance black powder cartridge shooters swage their primer pockets to accept small pistol primers or place a wafer of cigarette paper between the flash hole and the black powder for this very reason.

As I ran the tests, firing about 450 shots, some powders proved unsuitable for various reasons. It became clear that bullets in the 150 class were the best fit for achieving power factor, reducing wind drift and improving accuracy.

As I delved deeper into testing, I found that Hodgdon H-4350 consistently gave me the best results. It, paired with the Hornady 147-grain ELD-M bullet, worked the best in my rifle.

In the end, you need to find what works best for you and what builds confidence at the match, and someday you may be walking the prize table.

.jpg)

(pg 37).jpg)

(pg 38).jpg)

.jpg)