7x61mm Sharpe & Hart

Phil’s Masterpiece

feature By: Terry Wieland | October, 23

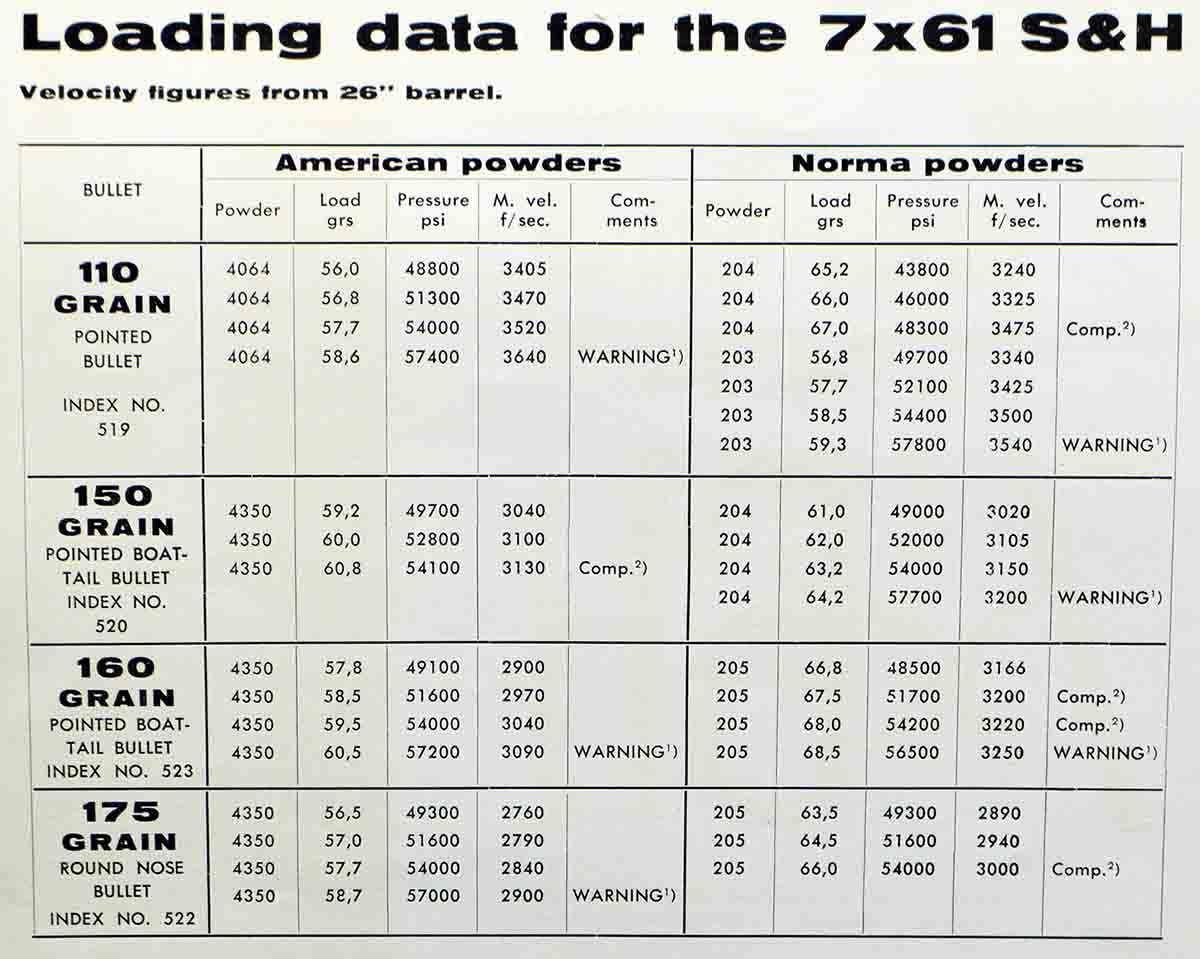

In the case of the 7x61mm Sharpe & Hart (S&H), introduced in the early 1950s, and first chambered in the Danish Schultz & Larsen bolt actions, the first is highly doubtful and the second nigh impossible. In terms of accuracy – especially factory ammunition in a factory rifle – it would be hard to beat even today. As for its ballistics, well, the published performance was one thing, the actual performance something else again. A 160-grain bullet at 3,100 feet per second (fps)? It didn’t do it then, and you can’t make it do it now.

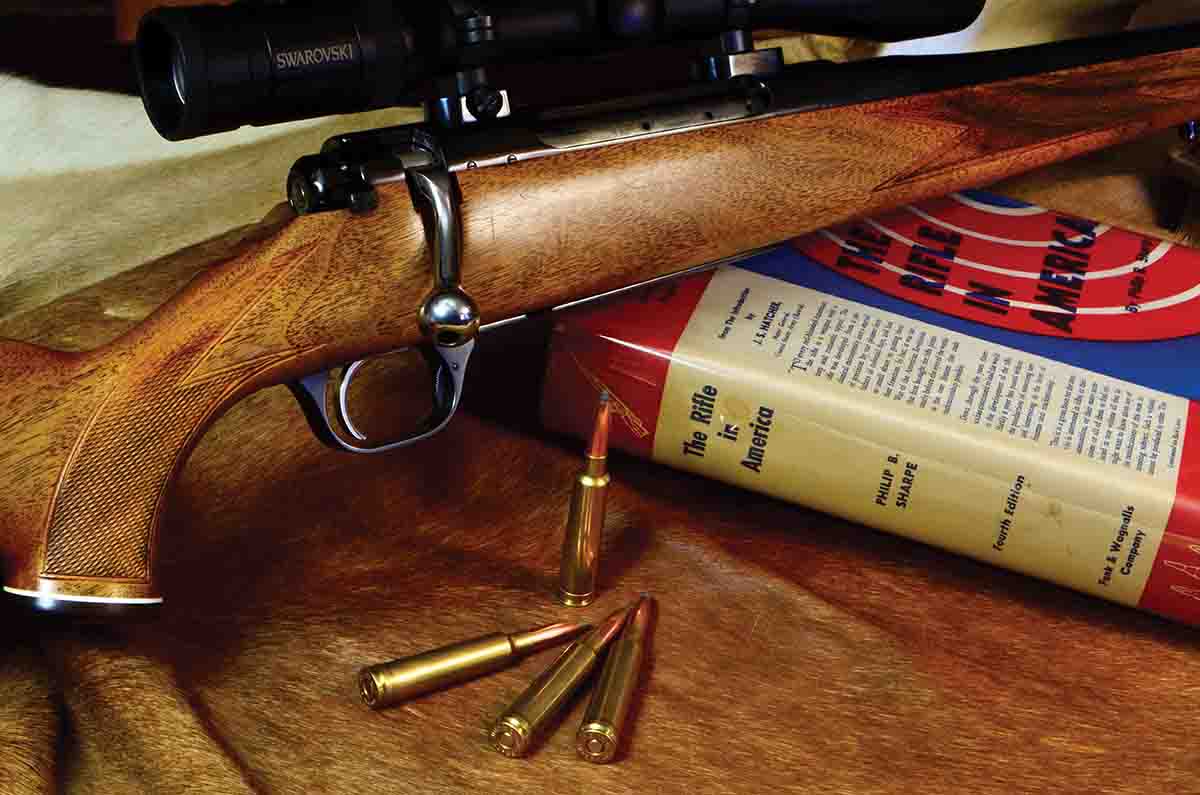

On paper, the whole venture should have been a smashing success: Philip Burdette Sharpe was a well-known American gun writer and ballistician, and author of two monumental – there is no other word – works on rifles and handloading: Complete Guide to Handloading and The Rifle in America.

The centerpiece was the cartridge. The 7x61mm Sharpe & Hart was, as the name indicated, a 7mm with a belted case 61mm in length and a sharp shoulder. During the war, serving as a captain of ordnance, Sharpe was assigned to evaluate ballistics work carried out by both friend and foe. Along the way, he encountered an experimental 7mm round developed by the French for a machine gun. Sharpe himself told the whole tale in a supplement to the fourth edition (1953) of his rifle book. Ken Waters covered it in “Pet Loads,” in Handloader in 1974, and since he knew Sharpe personally, his assessment can be taken as almost the final word.

Going by his description, since no photos are available, it was surprisingly modern: Short case, minimal taper, sharp shoulder, long neck to handle heavy bullets and, remarkably, no belt. Cases could be made by turning belts off 300 Holland & Holland cases, but Sharpe and his partner, Dick Hart, found this was too wasteful, so they simply left the belt in place, cut the cases down and blew them out. Thus was born the 7x61 Sharpe & Hart.

At the time, Schultz & Larsen of Denmark manufactured top-notch target rifles, and its free pistol was one of the few rivals to the Swiss Hammerli, which gives you some idea of their quality. S&L wanted to expand into hunting rifles, and developed a bolt action that departed from Mauser orthodoxy by using four locking lugs instead of two, and placing them at the rear of the bolt.

Over the course of about 15 years, the Schultz & Larsen rifles evolved into a very attractive and racy rifle, starting with the Model 54 and progressing through the models 60, 65, 65DL and finally, the 68DL. Even within models, certain features changed; it seemed, for example, they could never decide between a safety that went up and down, forward and back, or side-to-side. Such constant change and replacement is not good for sales.

The major problem, however, was the rear locking lugs. Although they made for an exceedingly smooth action, they were blamed for a tendency to case stretch, which was decidedly bad since handloading was almost a requirement for anyone owning the rifle. Today, if you don’t handload, you won’t be shooting a 7x61mm.

Then there was the Norma ammunition.

The final drawback was price: In 1965, the spiffy Schultz & Larsen 65DL had styling like a Weatherby Mark V and a price to match: $245 versus $285. A Remington Model 700 BDL (the flossiest model) cost $160 in 7mm Remington Magnum.

Since either the 7mm Weatherby or the 7mm Remington Magnum easily outperformed the 7x61mm Sharpe & Hart, it was no contest.

There were, of course, other factors. Norma was a foreign company, as was Schultz & Larsen, and a certain amount of chauvinism was reflected in magazine articles. There was concern about the stability of supply, an issue that has dogged Norma products in the American market ever since and with good reason. Some products, such as its excellent MRP powder, no sooner establish a following than they disappear from the market.

No American rifle company ever chambered the 7x61mm and, after the arrival of the 7mm Remington Magnum in 1962, there was not the slightest chance that one ever would. It’s ironic that one of today’s darlings is the 280 Ackley Improved, and the 7x61mm will do everything it will do and, truth to tell, a little bit more.

Both Norma and Schultz & Larsen tried to salvage something from this major project, but S&L effectively disappeared from the American market not long after. In 1968, realizing its ballistic shortfall was a major factor working against the 7x61, the company redesigned the case, thinning the walls and web to give it more interior capacity. This increased the capacity by about five grains of water, allowing more powder and hence greater velocity. At the same time, factory bullet weight was reduced to 154 grains from 160.

All of this made an already good cartridge a little better, but by that time the 7mm Remington Magnum had such a huge following, the Super 7x61mm (as it was now known) had no hope of catching it. Norma kept it in the lineup for another 40 years, offering brass and (sometimes) loaded ammunition, but finally abandoned it altogether a few years ago.

One should always check the headstamp, given the difference in case capacity and data is hard to come by. New data, for new powders, is almost nonexistent, and Hodgdon does not even include the 7x61mm in its reloading charts. Still, any data for the 7x61mm S&H from older Speer or Lyman handbooks can be used. You will probably get lower velocities to start with, but then work up. Unfortunately, some of the powders listed are no longer made. For example, Ken Waters did a piece on the Super 7x61mm in 1974, and obtained his best results with the long-since discontinued N-205.

As long as you can get H-4831 and IMR-4350, you’re not doing badly. For lighter bullets, I found that Hybrid 100V gives great results, which means you can work nicely with bullet weights from 120 to 160 grains.

In the 45th edition of the Lyman Reloading Handbook (1969), it was noted that the 7x61mm Sharpe & Hart (as it then was) proved to be “one of the most efficient cartridges we tested. Accuracy was good and velocities were extremely uniform. It produced very high velocities with minimum amounts of powder.”

Working with the “new and improved” Super 7x61mm in 1974, Ken Waters said much the same thing.

Not surprisingly, the good powders with the Super 7x61mm are H-4831 and IMR-4350 for the heavier bullets, Hybrid 100V with the middle weights. IMR-7828 will increase the velocity of the 160s, but: In my rifle, accuracy is not great, the bolt is stiff and the cartridge cases expand to the point where they do not chamber easily.

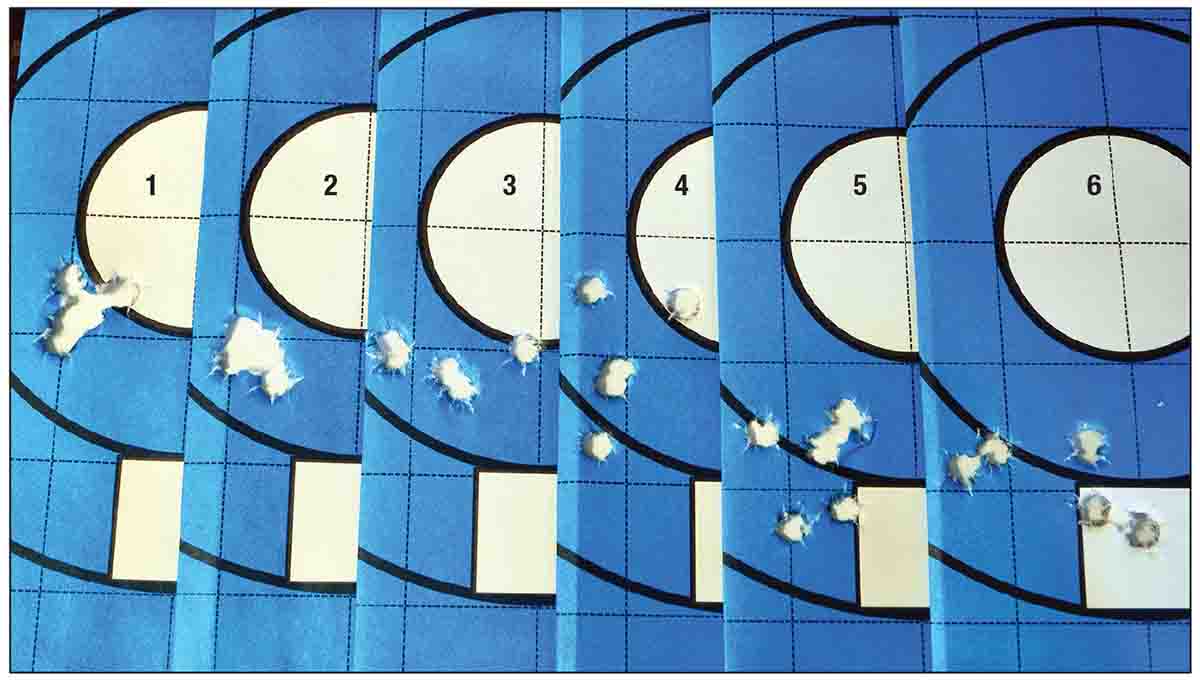

As can be seen from the accompanying table, the loads from 120 to 145 grains deliver excellent velocities and first-rate accuracy, with no sign of case stretching.

In fact, one could conclude – as Norma did in 1968 – that Phil Sharpe’s original determination to use a 160-grain bullet was not ideal. Norma dropped its factory bullet weight to 154 grains, and the 7mm Remington Magnum and 7mm Weatherby have both used a 150-grain loading for decades.

My standard hunting load is the one shown with H-4831 and the 160-grain Partition, but for game like pronghorns, or whitetails at long range, something lighter and faster works perfectly. The 120-grain Ballistic Tip would handle any varmint you can name.

One last thing to consider is barrel length. Data that does exist lists lengths from 24 inches (Speer), 25 inches (Lyman) and 26 inches (Norma). For reasons I cannot explain, Ken Waters had his custom rifle fitted with a 22-inch barrel, which guarantees substandard velocities. My Schultz & Larsen has a 25-inch barrel. Therefore, while paying close attention to the fine points of the data, don’t be surprised if your chronographed results differ from what you see listed, and sometimes by quite a bit.

In spite of its challenges over the years, the 7x61mm (Super or S&H) remains a fine cartridge, and one that deserved a better fate. It was a landmark in post-war hunting cartridge development.

.jpg)