Despite battlefield conjectures, wooden bullets were not intended as anti-personnel devices. Evaluation of Swedish wooden bullet training rounds shows they are unlikely to be effective even at bayonet distance.

Curiosity sometimes takes us to the fringes of handloading, where we don’t always enjoy complete success. So, let’s first address the question, “Why bother?” in this exercise of examining the possibility of handloading wooden bullet blank ammunition.

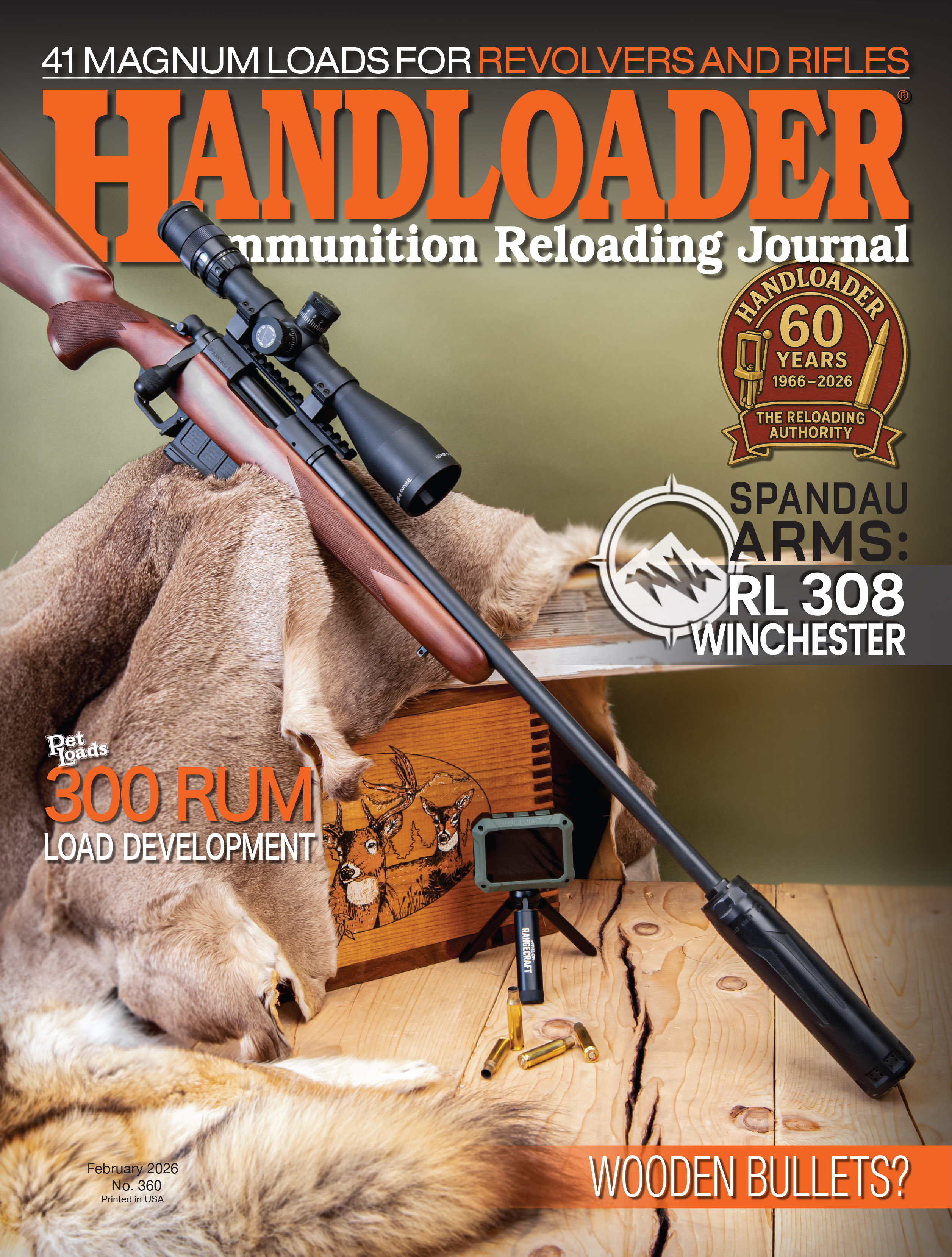

The test bed utilized here is the 6.5x55mm Swedish Model 38 Mauser featuring a muzzle threaded for a blank firing device (BFD).

In a lifetime of studying World War II history, I have occasionally encountered anecdotes about combat soldiers who found enemy rifle ammunition loaded with wooden bullets and assumed its purpose was to inflict egregious wounding. The logic behind the assumption is that while immediately dispatching an enemy soldier reduces the enemy’s manpower by one, wounding said soldier instead consumes the efforts of several more in providing first aid, removing him from the battlefield, and treating him behind the lines, reducing manpower by three or more. This argument presents the wooden bullet as a logistical weapon, if you will.

Bright red color immediately identifies these as Model 14 wooden bullet blanks for training purposes. They came in 10- and 20-round boxes loaded on stripper clips.

That assumption survives and continues to circulate today in third-hand anecdotes. While I would never presume to refute from my armchair the personal experiences of a combat soldier, note that such cartridges bearing wooden bullets were commonly manufactured as “blank” training rounds or for launching rifle grenades – even the U.S. Army utilized them for a period. Especially for the latter use, it’s reasonable that such wooden-bullet rounds found their way into a combat environment. Yet, ask yourself, “Would I choose to arm my soldiers with a wooden bullet that likely won’t effectively disable an enemy even if it hits him?” Your honest answer is a good indicator of reality.

Yet wooden bullets are in limited use today as a non-lethal method of crowd control. Law enforcement banally calls it “pain compliance,” in that the wooden bullets cause painful bruising and welting when striking a person and, though rarely, if ever, penetrating the skin, encourages the strikee to modify his behavior and go find something else to do.

Training with blanks lends realism to combat exercises; most armies have used them. As you’ve no doubt experienced, trying to feed a bullet-less cartridge case from a rifle’s magazine into the chamber can be a slow, fumbling exercise. One can engineer special bullet-less cases to make blanks (and they have been common for decades), but another resolution to the issue of magazine-feeding blanks for combat training was the wooden bullet. Here we have an example of Swedish wooden bullet blanks intended for use in the Model 1896 and Model 1938 Swedish Mauser bolt-action rifles.

Made of wood, the driving band diameter wasn’t critical and varied, bullet to bullet, quite a bit.

Bright red paint offers immediate visual recognition that these bullets are not garden-variety Swedish full metal jacket (FMJ) combat cartridges. Because no one is supposed to get seriously hurt during training, the cheerful red, wooden bullets terminate their brief journey by disintegrating against a blank firing device (

losskjutningsanordn) that screws onto the rifle’s muzzle (note that many, though not all Swedish Mausers, have threaded muzzles).

A hefty chunk of Scandinavian steel weighing nearly half a pound, the Swedish Mauser blank firing device (BFD) is composed of four parts and a single screw. A dozen holes perforate the circumference of the visible outer sleeve to vent gas and pulverize wood dust. A solid inner sleeve is the pulverizing anvil. This inner sleeve screws into the outer sleeve, and itself threads onto the rifle muzzle. Separation of the two sleeves isn’t readily possible, as the sleeve threads are peened with a pointed punch to prevent turning the inner sleeve, so I couldn’t make a more detailed examination of the device’s innards. A steel band circles the outer sleeve to hold a retaining clip that snaps over the rifle’s front sight, preventing the BFD from unscrewing from the muzzle during use. A screw retains the band and the clip.

Obviously, the BFD must thread snugly onto the rifle muzzle to prevent any gas and debris blow-by. Because threads start at different points among different BFDs and rifles, the retaining clip can be moved to mate up with and snap over the front sight. To properly install the BFD, swing the retaining clip up out of the way and screw the BFD down until it snugs up against the muzzle. If the retaining clip doesn’t align with the front sight, simply spin the clip and its band around the BFD until it does. If you must loosen the screw first, remember to snug it back down again.

The mixed headstamps within each box of ammunition indicate cases were likely previously fired and salvaged for the purpose of making blanks.

Can you imagine what might happen if someone were to fire a live round in the rifle with the BFD attached? Let’s leave that permanently to imagination, and never leave the BFD attached to the rifle when not actively in use. The Swedes could have painted the BFD bright red like the wooden bullets, but apparently decided that anyone dumb enough to shoot a live round with the BFD attached was too dumb to be in the Swedish army.

Blanks contain about 23 grains of a square-flake powder the Swedes called, “Rifle training powder 1.” Barely crimped in place, some bullets can be pulled from cases with the fingers.

Sweden’s designation for its 6.5x55mm wooden bullet blank cartridge is “m/14.” The blank sports a 6.5-grain pointed wooden bullet vaguely resembling the Swedish Model 94/41 139-grain FMJ spitzer bullet combat ammunition adopted in 1941 to replace the original Model 94 156-grain roundnose bullet. This Model 14 wooden bullet features a prominent driving band measuring 6.59 to 6.73mm (being compressible wood, it doesn’t need to be precise) and seated at the case mouth; diameter then steps down to about 5.7mm-ish in front of the driving band. The bullet base is hollowed out to about half the bullet’s length, probably to encourage complete disintegration.

Brass cases for these Swedish m/14 wooden bullet blank loads, I have read as unverifiable information, are allegedly once-fired cases and/or cases of inferior quality. I have found no information resourced from the Swedish military or blank manufacturers, or in reputable literature, confirming whether this is so. Yet, one clue to its veracity is that the box of Model 14 cartridges here is of mixed headstamps. As well, low-pressure blank ammunition seems a fiscally smart use for once-fired brass (prior to World War I, the U.S. Army recycled fired brass for gallery loads), so the claim is reasonable.

A great many Swedish Model 96 and Model 38 rifles have muzzles threaded to accept a BFD. A thread protector, or sometimes a muzzle brake, was installed to protect the threads when the BFD was not attached.

A 23-grain charge of a flat, square-flake powder launches the wooden bullet. The Swedish military designated the Model 14 powder, “

gevärsexerciskrut I,” or “

Rifle exercise powder I.” In this context, “exercise” can be translated as “training,” which clearly differentiates the m/14 powder from powder intended for standard combat Model 94 or Model 94/41 cartridges. Perhaps this “exercise” powder is so-designated because it has some inferior quality, making it unsuitable for combat cartridges, yet it is still good enough for training purposes. In firing here, the powder left an exceptional amount of fouling in the bore, requiring about twice the cleaning time and patches than if I had fired 50 rounds of standard ammunition in Vintage Military Rifle competition. Perhaps some of that fouling was actually soot from burned wood. A careful examination of cleaning patches showed no trace of wood particles or splinters left in the bore.

A great many Swedish Model 96 and Model 38 rifles have muzzles threaded to accept a BFD. A thread protector, or sometimes a muzzle brake, was installed to protect the threads when the BFD was not attached.

I had intended to replicate the Swedish wooden blanks, but somewhat surprisingly ran into a roadblock – a wooden roadblock. How does one make a handful of wooden bullets? Lathe-turning dowel rod comes immediately to mind. Lathe-turning wood is not among my many talents, but in consulting with an expert on the wood lathe skilled at making small pieces such as ink pen bodies, I learned that shaping a relatively tiny bullet to 6.7mm diameter and drilling that tiny hole into the base is not as straightforwardly simple as it appears to the ignorant. For this project, it turned out to be completely (OK, economically) unfeasible, and I speculate the Swedish wooden bullets must have been machine-stamped in some way, perhaps with the inclusion of an epoxy to withstand manufacture and subsequent use.

Buddha said, “Life is full of disappointment, get used to it,” or something akin to that, though he wasn’t referring specifically to handloading. What remains here, then, is to satisfy curiosity by shooting the original Swedish wooden bullet blank cartridge to note its performance with the BFD attached to the rifle. Beyond that, curiosity also demands some chronographing and shooting a paper target to determine whether a wooden bullet (this particular military wooden bullet and cartridge, anyway) has the Bollar and accuracy that it might be effectively used for anti-personnel purposes at battlefield distance.

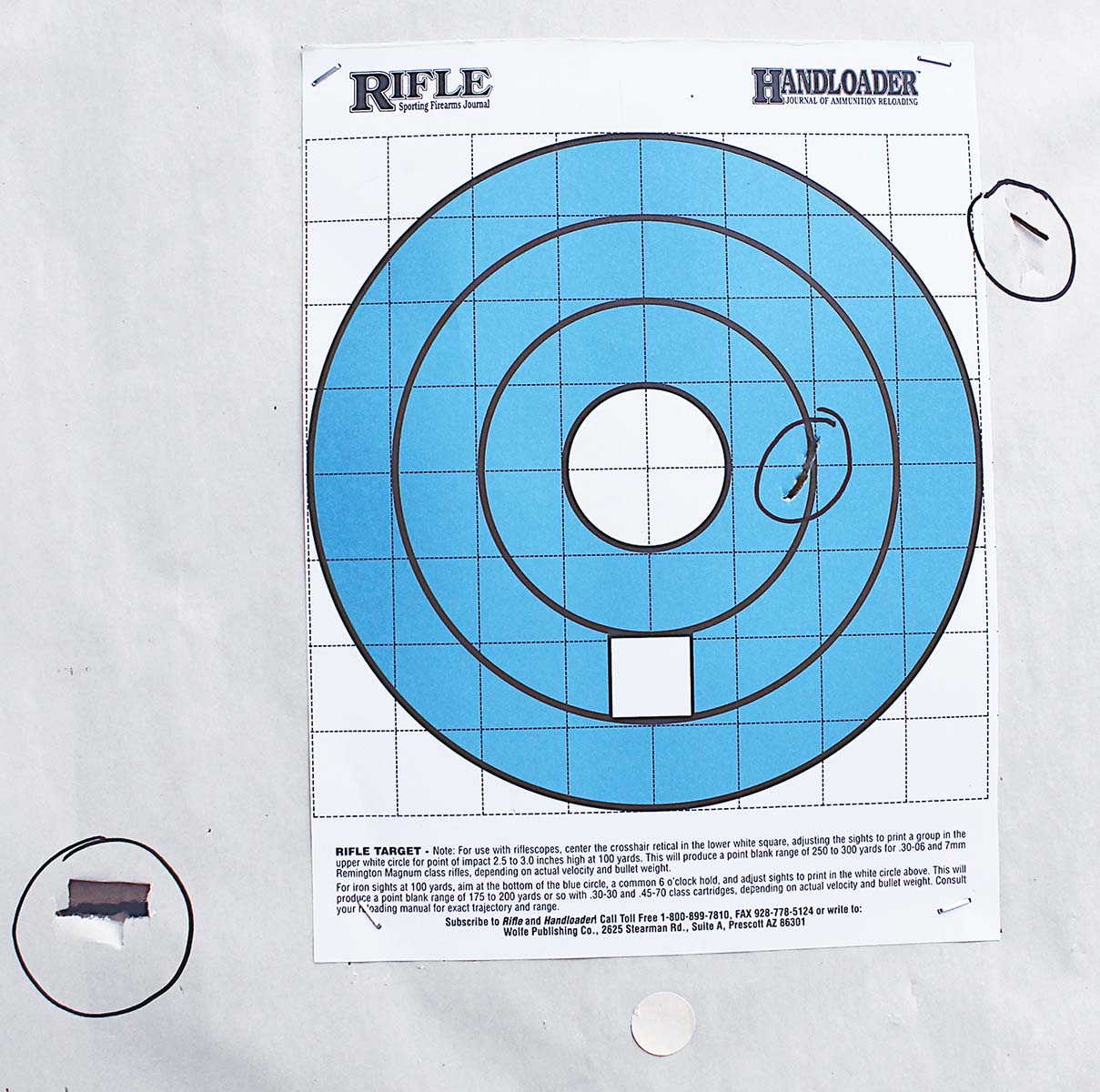

No wooden bullet or piece of bullet struck a paper target until it was only nine feet away. Splinters are circled on the right, and a bullet “keyhole” on the lower left. Three separate shots. Hold was standard six o’clock.

The test bed here is an original 6.5x55mm Swedish Mauser Model 1938 short rifle. First, I set up a paper target six inches to one side of the BFD attached to the muzzle. Upon firing, the muzzle blast could be seen to move the paper surface, but the BFD completely vaporized the wooden bullets, as not a splinter or even a particle of wood left a mark on the paper, and I convinced myself I could detect a faint smell of wood dust comingling with the smell of burnt powder.

Removing the BFD and moving the target out to 25 yards, no bullet struck the target, and it was the same at 20, 15 and 10 yards. Finally, at nine feet from the muzzle, a few wooden bullet splinters stuck in the target’s cardboard backing, and one bullet turned sideways to leave an elongated keyhole well off the left side of the target. As a side note, the rifle’s report sounded somewhat less than with standard ammunition, and recoil was nonexistent.

Five shots over the chronograph rendered velocities of 2,724, 625, 1,578, 987 and 1,807 feet per second (fps), with an extreme spread (ES) of 2,099 fps. We can attribute this bit of weirdness to the wooden bullets beginning to disintegrate immediately upon exiting the muzzle and the optical sensors of the chronograph clocking random pieces. Several other shots were recorded only as unresolvable errors.

The wooden bullets help cartridges to feed flawlessly from the magazine.

Curiosity satisfied here assures us that wooden bullets are not viable as combat ammunition even in a last-ditch situation, and so were never intended to be used in that role. Accuracy wise, I suppose if riot police were to fire enough wooden bullets into a crowd, some are bound to strike someone. Military wooden bullet blanks are old school, supplanted today by bullet-less brass cases shaped to ensure proper feeding from magazines and through belt-fed, fully automatic weapons.

These Swedish wooden bullet blanks and BFDs are still available with a little online searching, and are still reasonably priced if you want to conduct your own testing. But I wouldn’t wait too much longer. The days when I purchased my first Model 1896 Mauser from a milsurp house for $55 are past, and one day, it’ll be the same story for these wooden bullet blanks. When they’re finally all gone, so is your opportunity - unless you are a lathe-turner of tiny bits of wood or can figure out a fiscally reasonable way to make a wooden bullet.

.jpg)